Since Federal Housing Finance Agency Director Mark Calabria was approved by the Senate, he has set an aggressive timeline for shaking up the housing finance system by ending the conservatorship for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Calabria says that the status quo is no longer acceptable. He aims for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to begin the process of exiting conservatorship and rebuilding private capital by the beginning of 2020.

As Calabria approaches his task, the respected economist and former congressional staffer inherits a policy narrative that is cluttered with a variety of views and assumptions that may make sense within the confines of Washington, but may not jibe with the world of mortgage finance. Chief among them is the assumption expressed by some significant players in the discussion that we can have government-subsidized housing while reducing the taxpayer support for the GSEs and putting the emphasis instead on private capital.

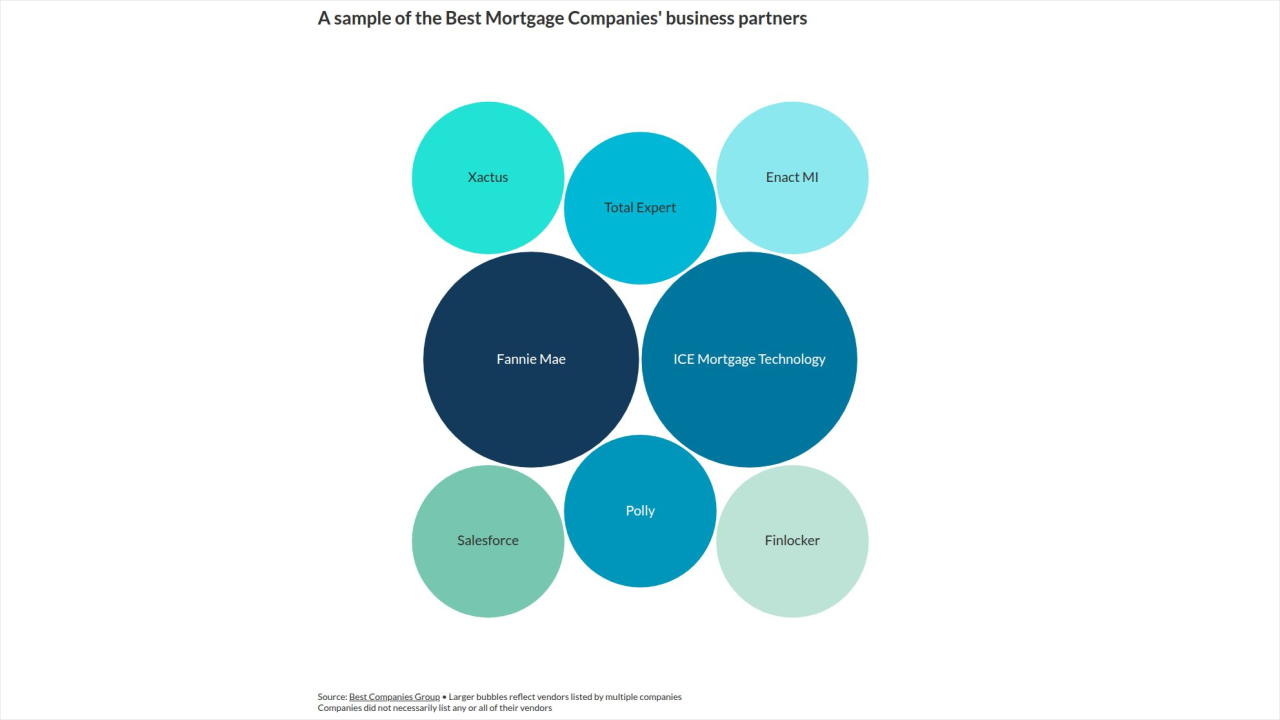

The objective, Mark Zandi of Moody's Analytics recently told an audience at the Urban Institute, is to preserve the benefits of the GSEs in terms of the price of credit and the availability of a 30-year mortgage, while reducing the risk to taxpayers via risk sharing and other measures. Indeed, our colleague Eric Kaplan of Milken Institute went so far as to say that private investors prefer and are more comfortable buying credit risk from Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac than investing in private mortgage loans, where they face first loss in the event of default.

What's interesting about this Washington narrative is the virtual absence of any discussion as to how these proposed administrative changes in the status of the GSEs could directly impact the world of mortgage finance for lenders and end investors. We talked about this issue in a previous comment (

The assumption that conservatorship can end without significant changes in how the GSEs operate may be the most dangerous assumption of all. Diana Olick of CNBC, for example, reported on May 29 that investors are already pulling back from GSE debt securities and MBS out of fear that under Director Calabria the government guarantee for the GSEs may be in question.

While there was a lot of discussion at the Urban Institute and previously at the Mortgage Bankers Association's National Secondary Market Conference in New York about restoring competition to the mortgage markets, there seems to be little appreciation as to how such changes will impact the credit profiles of the GSEs and, more important, the perception of investors.

Global investors know and trust the credit of Ginnie Mae, acting head Maren Kasper told the audience at the Urban Institute. Sadly, the same cannot be said about the brand of the GSEs with global bond investors. For example, under the present situation of conservatorship, both Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac have the same credit profile as Ginnie Mae — full faith and credit of the United States. Loans eligible for pooling for all three agencies are essentially government risk.

Once the Treasury exercises its warrant, sells its shares and thereby recovers its investment in the GSEs, the enterprises will then be quasi private federally chartered nonbank finance companies with a $250 billion combined credit line from Treasury. Almost overnight if not before, the credit markets will no longer treat the GSEs as the same credit risk as Ginnie Mae with its statutory full faith and credit guarantee.

At a minimum, the debt and mortgage backed securities guaranteed by the GSEs should reflect the 20% weighting assigned for the purposes of risk capital weights for US banks and insurance companies. Ginnie Mae securities, like Treasury debt, has a zero risk weight. Indeed, the Federal Open Market Committee may be legally obliged to sell its GSE MBS holdings once they are no longer officially "obligations of the United States."

So let's assume for the sake of argument that, under Director Calabria's administrative reforms, the cost of funds for the GSEs slowly increases above the spreads for Ginnie Mae securities — this to reflect the change in the credit standing of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Remember, once these entities exit from the conservatorship, they are basically private nonbank mortgage firms like Mr. Cooper or Quicken, with limited private capital and a credit line from the Treasury.

Will this significant legal change be reflected in the pricing of and haircuts applied to bank warehouse facilities and repurchase transactions for GSE eligible collateral? Would GSE loans financed via a repurchase transaction require a margin? Probably yes. That's a hint. Indeed, once the GSEs are again "private" nonbanks, Ginnie Mae will be a clearly superior credit and may have substantially better execution in the secondary market than the GSEs. What does this imply for housing policy?

"The idea that there is some amount of private capital that gets you to the same market acceptance as either conservatorship or an explicit guarantee from Treasury strikes me as wishful thinking," noted Michael Bright, CEO of the Structured Finance Industry Group and former COO of Ginnie Mae. "Any outcome that does not involve explicit credit support for the GSEs runs the risk that markets and particularly global investors will not accept it."

Another aspect of the administrative change for the GSEs anticipated under Director Calabria is an end to the special treatment under the Dodd-Frank rule for qualified mortgages. Under the rubric of enhancing competition in the mortgage finance space, some policymakers advocate ending the so-called patch under the QM rule that treats all agency mortgages as coming under the legal safe harbors in the QM regulation.

"The exemption, known as the GSE 'patch,' sunsets in January 2021 or when the conservatorships end, whichever comes first," Kate Berry

When asked how much of the current flow of GSE mortgages would be affected if Calabria declines to renew the QM patch, one of the leading bankers in the mortgage securitization market said 30% at a minimum.

"These mortgages would either end up on banks' balance sheets, in private-label RMBS deals or not being made at all," the banker told NMN. "The private-label market could not absorb the full amount." The chart below shows the distribution of the $15 trillion in total outstanding mortgage debt, including roughly $5 trillion for the GSEs, $2.5 trillion for banks and insurers, $2 trillion for Ginnie Mae.

Should Calabria decide not to renew the patch, the volumes of loans moving through the GSEs could be substantially reduced, detracting from the ability of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to achieve profitability and, it is hoped, build private capital. Other possible changes known to be under consideration include prohibiting the GSEs from guaranteeing loans on second homes and investor properties, both initiatives that would reduce volumes and profitability.

The prospect for change in the credit status and business models of the GSEs may seem like a safe area for policy consideration in Washington, but the reality is a little more complicated in the world of mortgage lending and finance. There are people in Washington who seem to believe that the GSEs can operate as they do today without a federal credit wrapper, but even a cursory conversation with lenders and bond investors suggests just the opposite. As we noted in our previous missive, be careful what you wish for Director Calabria, you may get it.