Proposed changes to the Community Reinvestment Act could serve as a catalyst for banks to become more active in financing projects inside Opportunity Zones, according to some development experts.

Opportunity Zones provide tax incentives to investors in development projects located low and moderate-income neighborhoods.

They were created as part of the 2017 federal tax cut to stimulate development in distressed areas, but banks’ involvement, so far, has been limited because of uncertainty over whether business loans qualify for the tax credits.

Under proposed changes to the 42-year-old Community Reinvestment Act, any type of lending conducted in Opportunity Zones would qualify for CRA credit.

The proposal is intended to “encourage banks to conduct more CRA activities and to serve more of their communities, including those areas with the greatest need for economic development, investment and financing needs, such as … opportunity zones,” the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency said in the 240-page notice of proposed rulemaking released last week.

John Hope Bryant, the president and chief executive of the nonprofit Operation Hope, said it simply makes sense for banks to receive CRA credit for lending in Opportunity Zones. Developers need low-cost capital, and banks have it, so “it’s a marriage made in heaven,” Bryant said.

But not all community development advocates are as enthused about the changes as Bryant.

Some are concerned that will end up encouraging banks to make loans in areas that are already gentrifying, at the expense of the neighborhoods that most need the investment.

A group of community reinvestment groups, including the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, said in a joint statement last week that the proposal “utterly fails to achieve what were supposed to be the primary objectives of rule changes: greater clarity for lenders and better results for low- and moderate-income communities and people of color.”

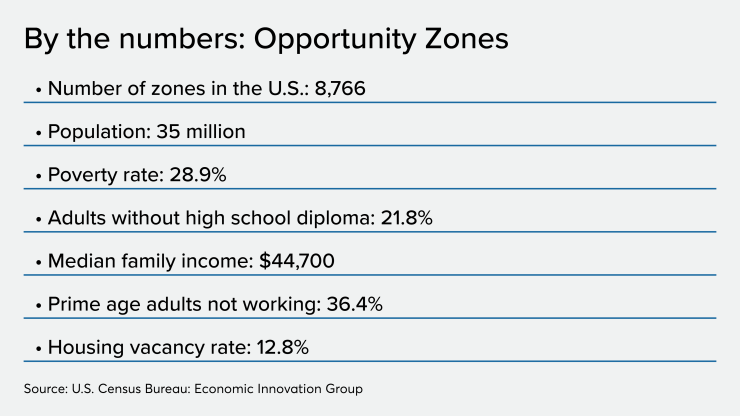

More than 8,700 census tracts in the U.S. and its territories have been designated Opportunity Zones, but not all would be classified as down-and-out. Bloomberg reported this week that at least a dozen National Football League stadiums are located in Opportunity Zones and noted that under the proposed revisions to CRA, banks could receive CRA credit for financing improvements to a stadium, such as new scoreboard or sound system.

Still, others note that the vast majority of Opportunity Zones are in dire need of investment. According to U.S. census data compiled by the Economic Innovation Group, the median household income in areas designated as Opportunity Zones is less than $45,000 a year and about 29% of residents live in poverty.

Steve Glickman, the CEO of Develop LLC, a Washington firm that consults with developers on Opportunity Zone projects, said that the proposal would enable banks to receive CRA credit for many different types of projects located inside Opportunity Zones, including affordable housing and workforce housing,

“Having more banks engaged in this process will really help increase the amount of affordable housing,” said Glickman, a former economic adviser in the Obama administration.

The rewritten CRA could also stimulate banks to provide low-cost loans to entrepreneurs who live and work in Opportunity Zones, Bryant said. Small-business lending is an essential part of redeveloping struggling neighborhoods, he said.

“People in these neighborhoods are used to the only vehicle for loans coming from check cashers or car title lenders,” Bryant said. “This could help bring in long-term equity that’s lower cost” from banks and other lenders.

But one expert on federal tax credits is not convinced that the new CRA will attract banks’ participation in Opportunity Zones. The zones need to attract equity investors before banks will make loans, and that is an ongoing challenge in many urban and rural areas, said Michael Novogradac, managing partner of the San Francisco accounting firm Novogradac & Co.

“Equity is a greater challenge" in low- and moderate-income neighborhoods "and equity is generally needed first to get debt financing,” Novogradac said.

Jeannine Jacokes, the CEO of the Community Development Bankers Association, said her biggest concern is that banks will focus only on projects that promise the highest and fastest return on investment.

Under the current CRA law, banks must demonstrate the connection between their financing activity and how it helps low- and moderate-income individuals, Jacokes said. The CRA proposal removes that requirement.

“This will encourage banks to do things in Opportunity Zones, but it will exacerbate the concerns about gentrification,” she said.