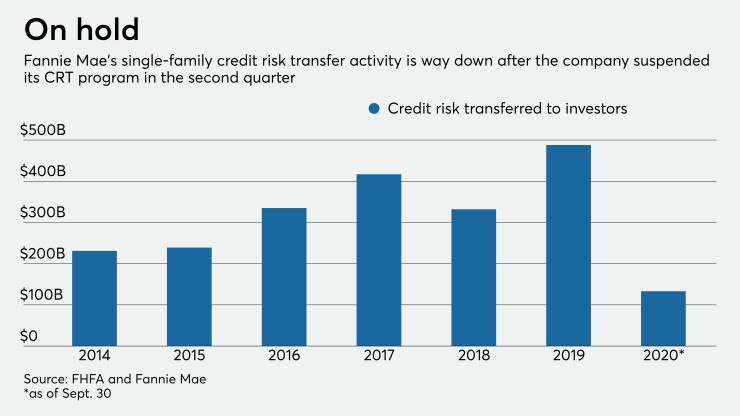

WASHINGTON — The mortgage giant Fannie Mae has drastically curtailed transferring credit risk to private investors this year, a move that industry veterans say could hurt taxpayers as the Trump administration tries to relinquish control of the government-sponsored enterprises.

The shift is partly due to

“That means that risk is concentrated back on the balance sheet of Fannie and Freddie, and that's leaving more of it being absorbed by the taxpayer,” said Ed DeMarco, president of the Housing Policy Council and former acting director of the FHFA, who started the credit risk transfer program in 2013.

Credit risk transfers allow Fannie and Freddie to sell a piece of loans they guarantee to private investors. The deals have become a hallmark of the federal conservatorship of the two companies because they mitigate potential losses should a loan go bad. This has historically been important to the government, which bailed out the GSEs in 2008 and to this day owns a majority stake.

Both companies suspended CRTs in the second quarter when the coronavirus pandemic hit the markets and fewer investors wanted to take on more risk. But whereas Freddie resumed the deals in the third quarter, Fannie did not and says it has no plans to in the short term.

Fannie's suspension of the program could violate regulatory standards set forth by the FHFA, meaning the move could have consequences for the company.

Some market participants say the FHFA's post-conservatorship capital framework is a likely cause for Fannie's decision. The rule was finalized just last month and will not go into effect until the GSEs are freed from government control, but the companies likely started laying groundwork to prepare for the new regime after it was proposed in May.

The rule not only provides just modest capital relief for credit risk transferred to investors, but the GSEs will also face higher capital requirements for credit risk they retain in the deals.

Many say that will discourage the GSEs from transferring risk altogether. The concentration of risk at the two companies when they exit conservatorship could threaten massive losses should a wave of borrowers default.

“We kept pushing in our thoughts with respect to GSE reform that we thought credit risk transfer was a good idea, and if anything, it should be expanded,” said Mike Fratantoni, chief economist for the Mortgage Bankers Association.

The past and future of credit risk transfer

When he ran FHFA, DeMarco had two goals in creating the CRT program: shift risk away from Fannie and Freddie and attract more private capital to the mortgage market.

“What that was going to do over time, it was going to shift Fannie and Freddie away from a principal world of guaranteed mortgage credit into more of a role in intermediating in the mortgage market to be able to figure out structures to sell that credit risk off into private hands,” he said. “That would bring more private capital, which protected the taxpayer, and it would create more market signals and market pricing.”

Through the program, Fannie and Freddie have transferred more than $100 billion of risk to the private sector. To this day, the FHFA’s scorecard — which it uses to evaluate the GSEs — requires the companies to “transfer a significant amount of credit risk to private markets in a commercially reasonable and safe and sound manner.”

Industry observers have long argued that Fannie and Freddie should continue CRTs even after they are re-privatized because the transactions reduce the risk on the companies’ balance sheets.

So many were puzzled when the FHFA unveiled its proposed post-conservatorship capital rules for Fannie and Freddie in May, with a higher capital charge on the exposure a GSE holds in a credit risk transfer. Commenters felt that would disincentivize the use of the program.

Even Freddie argued that the FHFA should rethink the policy.

“The capital framework should recognize the risk-reducing nature of CRT and the historical policy support provided by the FHFA and Treasury to develop the CRT program,” wrote Ricardo Anzaldua, executive vice president and general counsel at Freddie, in a comment letter on the proposal.

The final rule issued in November tried to address some of the concerns about the treatment of CRT by adjusting the risk weights on the credit piece that the GSEs retain in a transaction, among other steps. But most observers felt that the changes were too modest.

“I think I, like most people in the industry, found it pretty curious, maybe counterintuitive, that the capital rule didn't treat CRTs more favorably,” said Tim Rood, head of industry relations at SitusAMC. “The final rule gave us some credit, but that credit was really taken away by the other buffers that are in place.”

Despite the minor adjustments, some blasted the final rule for magnifying the mortgage giants' risk.

"Among other consequences, the GSEs are now strongly incented to re-concentrate extraordinarily large amounts of mortgage credit risk back onto their balance sheets, which would likely be the single most backward and damaging systemic risk action since the 2008 financial crisis," wrote Don Layton, former Freddie CEO and a fellow at Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies, in a blog post.

Dennis Lee, an analyst at Barclays, doubted that the changes would be enough for Fannie to resume credit risk transfer through the issuance of the company's Connecticut Avenue Securities.

“I think that one of the primary motivations for Fannie to issue CAS deals was really for capital relief, as opposed to a loss mitigation strategy,” he said.

'A business decision’

At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, Fannie and Freddie suspended CRT transactions as it became more challenging to transfer risk to already risk-averse investors. Neither company engaged in any CRT in the second quarter.

In the third quarter, however, Freddie resumed CRT through its Structured Agency Credit Risk offerings.

“After taking a pause to assess the impact of the pandemic in the second quarter, Freddie Mac’s CRT program came charging back in the third,” said Mike Reynolds, vice president of single-family CRT at Freddie, in a statement.

But Fannie took a different approach.

The company said in its third-quarter filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission that “although market conditions improved in the third quarter of 2020, we did not enter into any new credit risk transfer transactions in the third quarter and currently do not have plans to engage in additional new credit risk transfer transactions in the near future.”

Fannie cited the FHFA’s capital rule among other factors for its decision and only said the company would “continue to review our plans” in the near term. The move shocked some observers because the capital rule will only be triggered once the GSEs are released from conservatorship. By all accounts, that won't be anytime soon.

“The market for CRT was already well on its way to being fully restored by late April and into May, and we did see Freddie Mac get back into that,” DeMarco said. “So, to my mind, I think that Fannie should have resumed undertaking credit risk transfer transactions this summer.”

Fratantoni and DeMarco said the decision was a cause for concern.

“It's what we and others predicted in our comments that if that capital rule goes into effect, there's just not a lot of benefit in terms of optimizing use of capital from doing credit risk transfer,” said Fratantoni. “I think from a systemic risk standpoint, that's the wrong way to go to once again concentrate risk of the GSEs as opposed to distributing it across the market.”

Fannie Mae declined to comment on the record for this story.

Moving in two different directions

CRT transactions are a requirement included in the scorecards that the FHFA uses to evaluate the GSEs. An FHFA spokesperson noted that the GSEs not meeting those goals could affect executive compensation.

“As conservator, FHFA expects the Enterprises to meet all the goals in their scorecards, including the issuance of CRT,” the spokesperson for the agency said. “The CRT market is an important tool that the Enterprises use to manage their risk and capital, especially while they are undercapitalized.”

DeMarco said that the FHFA has the ability to be more forceful.

“As the safety and soundness regulator, FHFA as the conservator certainly has the capacity to say, ‘It's time for you to be back routinely in this market,’” he said.

Compared to Fannie, the loans in Freddie’s single-family book of business with credit enhancement only dropped slightly to 52% as of Sept. 30.

It’s unclear why Fannie and Freddie are moving in different directions on CRT. Freddie could perhaps see some value in CRT transactions beyond just capital relief.

“It's possible that Freddie came to the conclusion that in a bad enough housing scenario, these CRT, their STACR deals, would provide real credit protection and they would be able to transfer a lot of losses to private market investors,” said Lee.

But the dissonance may only be temporary, said Rood.

“Freddie didn't take the same path, but I think they'll end up in the same place,” he said. “If there isn't a sufficient offset from a capital perspective, I don't envision either one of them making a business decision to sell off the credit risk.”

'A different form of protection'

But not everyone is sounding the alarm. For one, FHFA Director Mark Calabria has said the GSEs need to build up a substantial amount of capital in order to exit conservatorship. Some feel that it would be impossible for Fannie and Freddie to accomplish that without taking on more risk.

“So long as they're building capital, and they have a reasonable capital buffer, I don't think there's anybody in the business that is better at credit risk management than the GSEs, so I have supreme confidence that they'll do it responsibly and that they'll charge what they need to charge for it, so I'm not concerned about that” said Rood.

Lee also noted that a wider capital buffer could protect the GSEs from losses just as the CRT transactions are intended to do.

“That's just a different form of protection, so you effectively build up your equity capital as opposed to using CRT as a capital buffer,” he said.

Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin alluded to that point Wednesday at a House Financial Services Committee hearing.

"I think credit risk transfer is a very effective mechanism of supporting the institutions," he said. "I also think that capital accumulation is something that is very important and ultimately capital raising so that taxpayers are not at risk."

The GSEs are not operating under the capital rule just yet and are only allowed to hold up to $45 billion combined in capital. That means Fannie is not currently receiving the benefit of a wider capital cushion or credit risk transfers, which could leave taxpayers exposed in the interim.

But with President-elect Joe Biden’s inauguration less than two months away, and many expecting Calabria to be on his way out, the future of the capital rule is in doubt. Therefore, Fannie’s economic calculus regarding CRT transaction may also be in flux.

Biden’s incoming administration could attempt to replace Calabria

“On the CRT front, it's a similar kind of motivation on both sides, where you see both Democrats and Republicans wanting the GSEs to transfer a lot of their credit risk to private market investors, and I think that a Biden-nominated FHFA director is going to hew to that philosophy,” said Lee.