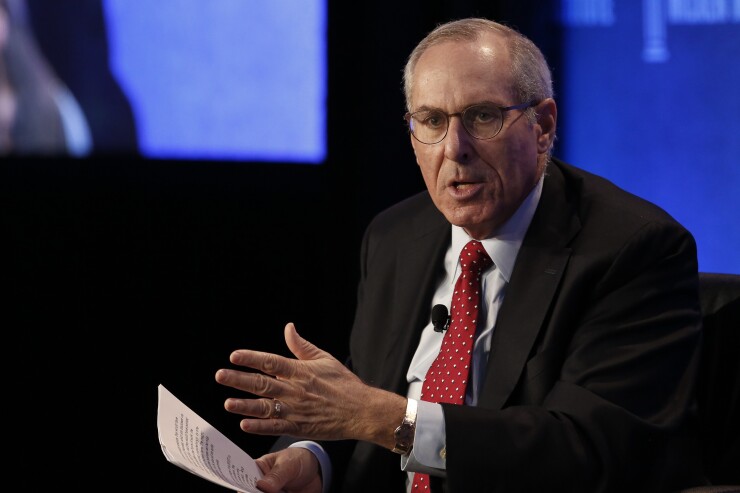

WASHINGTON — Donald Layton has just under a year before he retires as CEO of Freddie Mac after more than 40 years in the financial services industry, but the coming months are shaping up to be some of the most formative at the company since Layton joined in 2012.

In June, both Freddie and Fannie Mae are slated to roll out

And just next month, the comment period will close on

Layton sat down with American Banker during the Mortgage Bankers Association annual conference to talk about what he has learned from his experience and what to expect before he retires.

This interview has been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

What is in store at Freddie between now and your retirement?

DON LAYTON: Obviously, there’s the priority of succession. I’d like to point out that we have triple succession, not just me. There’s me, there’s going to be a new head of the FHFA, and how much that’s a change, we don’t know. We’re going to find out. The third is, just by coincidence, our board chair.

Despite that, if the government, and I mean government very broadly, is spending time on housing finance reform of the future, we have a brand as the best technical advisers around town, because it’s a very complicated business, so a priority would be to help them.

Competitiveness is built into our DNA—I just have to keep it going. We’re starting to think a little bit about the down cycle. It’s been a great run up. I don’t think there’s going to be a strong down cycle, but we have to be prepared for it.

Whatever we can do to help to land [the proposed rule on enterprise capital] and bring that to finality is important to us. We’re an expert on that, we care about it a lot and we developed the kind of father to the system that eventually came out. The comment period ends the middle of next month. The finalization of it should tie in … with my retirement.

It’s been an exciting five years. The last five years and the next five years is very exciting in the mortgage business. It’s a very contorted and old-fashioned business that’s become modernized in all these ways. It’s great. If you go talk to someone who’s in a major mortgage company, they’ll tell you there’s been more change and innovation in the last five years than in the last 25 years.

How has Freddie Mac changed as a company since you started?

Remember, I took this as public service; I already had my career. I was not trying to burnish my resume.

Simple fact is Freddie Mac, the GSE system, which I experienced back as a banker, was not very competitive, not very commercial. It was very policy-driven, ex-government agency style and I’m not an apologist for the old system. They did some good stuff, and they did some things that eroded confidence. They made themselves political issues because of the unlimited investment portfolios being used.

It became, "Help build something that we can be proud of," where you took the core value that you’re there for as a mission and operate it well. That’s what led to credit risk transfer, the capital system—all those things. That’s largely done.

I have said this before: History books like to declare eras. My era was the era of: Make the companies work well in conservatorship. Prior to when I got there, they were still dealing with the foreclosure crisis and were not able to focus on solutions at all. And the foreclosure crisis kind of peaked, and it’s still around, but the thought process was moving away. … It was make quality companies that can do the job well.

What role should Freddie play in housing finance reform?

We do not determine our destiny. We should be great technical advisers to everyone working on it and we should execute well, and that’s the role of the company. We’re not supposed to be in there lobbying for one solution or another. The only thing you’re supposed to be lobbying for is something that works over something that doesn’t work, because you have good technical. It’s not like you have a big conflict of interest. The FHFA’s in charge and you get paid in a way that doesn’t make it a conflict of interest.

Part of Freddie Mac’s mission is to make homeownership more affordable. How has Freddie Mac done that so far, and how will it continue to do that?

There’s a big squeeze. House prices bottomed out in 2011, and depending on your index, have grown about 5% since then. That is higher than nominal incomes, which means on average in America, housing is more expensive relative to your income, and this is usually most visible in renters paying larger percentages of their income to rent. It’s easier to see than the cost of owning a home, which has lots of components, and so the percentage of people’s income that they’re spending on their residences are going up and up and squeezing everyone else. That’s not good. Ideally, we’d like the cost of housing nominally to go up with the nominal incomes, certainly not higher, the way it has been. We are a policy organization.

There are laws about us. We should be helping affordability; we’re not supposed to be a honey pot for politicians to raid and give money away. The FHFA direction is clear. There should be quality credit … and it should be sustainable. … Now then what the FHFA wants us to do, which we love, is be creative about how to create more housing, which we can finance a little bit, more in the multifamily space, and work some of these programs to help affordability. I don’t pretend they’re going to be the giant solution to years of house-price growth being part of income, but definitely at the margin it can help.

A Senate hearing scheduled for Oct. 18, which was postponed, had been expected to look at so-called "mission creep" concerns about the GSEs. What were you planning on saying at that hearing?

In terms of the Senate [Banking] committee’s angled attack, we would have told them as we have said to other venues … our job is not to spend our time worrying about what the new system could be. It’s to make the current system as best it can under existing laws. That’s our job in conservatorship. We think we’ve done a great job of that. That means following the congressional initiative given to us in the charter [and] that means adhering to limitations on the charter.

This is not a minor, quick, superficial process. Everything’s charter-compliant, everything goes directly to the mission, which we summarized in three words: liquidity—we buy from the primary market, stability—we have the system being more stable, and affordability—we try to keep this process possible.

The FHFA does not let us do stuff just to aggrandize or buy a market. It has to have that mission social value to it where it does something about affordability. IMAGIN is a classic. It solves stability issues, it solves affordability issues [and] it’s cheaper to the borrower in the long run. And technically, the certainty of getting paid is higher with IMAGIN than traditional [mortgage insurers] because there’s no separate rescission ability.

How much of a say do you have in the hiring process for the next CEO?

The answer is I have a modest say. The hiring is a triple-level hiring: board, FHFA and Treasury as opposed to a normal corporate board. I am a member of the board, so I get a kind of say. … I help them construct the process. There’s a search committee on the board, and I’m not on that. It’s all subject to FHFA approval at the end of the day.

What advice do you have for your successor?

Build up what we have. Remember the people and the management team at the core, because you can’t do it all. The easiest thing about being a CEO is you’re not in charge of the business, you’re in charge of people who are in charge of business.

It’s high-quality team first—by the way, that is going to be an issue, because we do have a lot of people who are older at the top. Ages begin with a 6. The next person is going to have to review management teams, your internals and your externals. High-quality cooperative team, remember the culture and be for the good of the system. Don’t just be another guy trying to make a buck off the system.

What’s next for you?

When this is over, I’ll be 69 years old. I’m not going to work full time again. I was already retired. This is my third retirement, so now I’m old.

I’ll do what’s called a portfolio of activities, where you have a life. I may join a board or two although my age may be involved in there in terms of term limit. Maybe do some nonprofit work, which has been hard for me with the back-and-forth between New York and here, and some investing.

I am highly likely to try and stay involved as an outsider in housing finance policy. I find the gap in knowledge between an insider versus the general outside policy community to be quite large, and so at least for a few years, I will be in a position to really help the debate, I think. I’m examining everything from writing a book, to doing the blog posts, to joining a think tank—those are not mutually exclusive. In this job, I’m restricted in what I can say outside, but once I’m out, then I can help.