Banks are still holding on to scores of delinquent mortgages that date to the real estate crash, but a surge in home values across the country is motivating them to more quickly move the most troublesome loans off their books.

Over roughly the past year, banks have been ratcheting up repossessions of foreclosed homes to the highest level in four years, according to the data firm RealtyTrac. Banks repossessed a total of 449,900 homes in 2015, up 38% from a year earlier, as they aim to capitalize on improving economic conditions and finally push their most seriously delinquent loans through to foreclosure.

"Whether it was an intentional strategy or a reactive one, we're seeing the final stage of 'extend-and-pretend' play out said Daren Blomquist, a vice president at RealtyTrac, referring to banks' proclivity to extend the terms of a loan and work with a borrower rather than taking possession of a property.

To be sure, banks have sold off billions of problem loans to hedge funds and private equity firms since 2010, both to bolster their balance sheets and to avoid the reputational risk of foreclosing on borrowers.

"Nonperforming loan sales have been a way for banks to avoid the scrutiny that comes with high foreclosure numbers because it's shifting the distressed loans to less-visible entities that end up foreclosing and the homeowner ultimately losing the property in some way," said Blomquist.

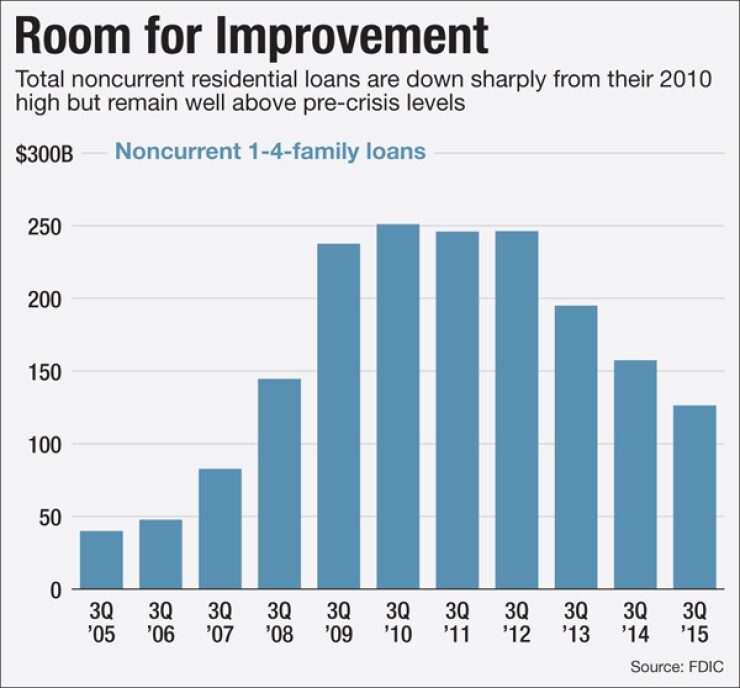

But they also held on to large numbers of loans, again partly to help keep borrowers in their homes, but also because they were waiting for home values to rebound, as they have in many areas. At Sept. 30, the amount of nonperforming loans on bank balance sheets accounted for 4.05% of all residential loans, well below a peak of nearly 8% in 2010, but still six times higher than it was in 2005.

Repossessions largely came to halt in 2010 after the robo-signing scandal rocked the mortgage industry. When bank employees were found to have routinely signed foreclosure documents without verifying their accuracy and absent a notary, as required by law, banks agreed to foreclosure moratoriums. By 2012, the top five banks had signed the $25 billion national mortgage settlement, agreeing to aid borrowers with foreclosure alternatives.

Still, some bankers have expressed surprise that banks have been so slow to move these problem assets off their books given the drain they've been on earnings and bank resources. Banks' reluctance to foreclose on properties also kept inventory levels artificially low, slowing the housing recovery.

"It is shocking to me that any responsible management would continue to carry any problem assets so long after the recession," said Mark Mason, the president and CEO of $4.9 billion-asset HomeStreet Bank in Seattle.

Lengthy foreclosure timelines in judicial states, where foreclosures are processed through the courts, also have played an outsized roll in failing to resolve distressed loans in a timely manner.

Much of the backlog is confined to three judicial states — Florida, New Jersey and New York — where it takes nearly three years to foreclose on a borrower.

Because of the huge backlog of foreclosure filings, many states have been under pressure to clear out cases.

Matt Weidner, a plaintiff's attorney in St. Petersburg, Fla., said he has recently seen an increase in bank repossessions despite pleas from both servicers and borrowers to have judges cancel foreclosure sales.

"Servicers are experiencing real conflict because they are sending their attorneys into court every single day begging courts to cancel [foreclosure] sales only to be told by judges to clear the foreclosure cases," Weidner said. "Banks are taking homes back in numbers that aren't rational."

RealtyTrac's Blomquist suspects that repossessions are on the rise because banks are under pressure