With the pre-crisis years a more distant memory, banks are embarking on a new chapter in construction lending where high demand and automatic profits are being replaced with patience and good old-fashioned conservatism.

"The philosophy" used to be "'Build it and they will come,'" said Daniel Hill, a senior vice president at Regions Bank. "We don't do that anymore."

In the wake of many banks no longer offering acquisition, development and construction loans following the crisis, institutions now are attempting to re-position the business to deal with a new type of market.

Demand is nowhere near where it was during the boom and lenders are still somewhat chastened by what happened in the crisis. But banks say they have found success taking steps like requiring more equity from builders and developers, financing smaller developments and offering terms meant to prevent builders from abandoning a deal.

But improving conditions in the ADC market may be assisting banks as well. Some institutions say demand is coming back slightly and construction volumes are up. Community banks and nonbank firms are even finding ways to compete with the biggest lenders.

As a result, banks are beginning to ease up somewhat on loan-pricing for "pre-sold" homes — where a builder has a buyer before construction begins — and are making more "spec" loans to provide financing to a builder before a homebuyer is lined up.

"There is still volume opportunity that we think will continue to recover on a reasonably stable low sloping growth curve," said Bird Anderson, who heads Wells Fargo's homebuilder lending unit.

New-home construction for single families peaked at 1.7 million housing starts in 2005, but starts plummeted in the crisis, dropping to 622,000 in 2008. Many builders went bankrupt and lenders spent considerable time working out defaulted construction loans. And the market may never fully rebound. Last year, 1-4 family housing starts totaled just 648,000.

Now banks are being conservative in ways beyond just demanding more upfront equity from a developer or builder.

Right before and during the crisis, developers had commitments from builders to buy and build on the lots. But the builders simply walked away when the market went south, leaving the developer holding the bag and the bank in most cases with a nonperforming loan and a lot of dirt.

"We learned a lesson from that," Hill said. "The way we do land acquisition and development lending is different than what it was in the run up to the boom years of 2003 and 2006," he said.

Regions will make development loans to "builders who are developing the lots for their own account to build on themselves," he said. In addition, the loans are smaller to developers just 40 to 50 lots at a time as opposed to 200 at a time, for example. "We prefer smaller bits," Hill said.

The bank will also in some cases require a builder to enter into a joint venture arrangement with the developer. "The contract requires the builder to purchase all or most of the lots, so the builder is on the hook," Hill said.

With banks being more conservative and conditions easing up a bit, Anderson said more lenders have entered the ADC market over the past two or three years. "But they are not flooding in," he said.

Wells is beginning to offer spec loans, but Anderson said the bank is still being cautious. He said they review such applications on a case-by-case basis and try to make a market determination of the expected absorption rate, which is the speed at which newly built homes are being sold and occupied.

"If absorption is increasing we might allow more spec homes. If it is not increasing then we don't," he said.

David Ledford, senior vice president for housing finance and regulatory affairs at the National Association of Home Builders, said banks are starting to lend again "but they are being selective" and "they want more equity in the deal."

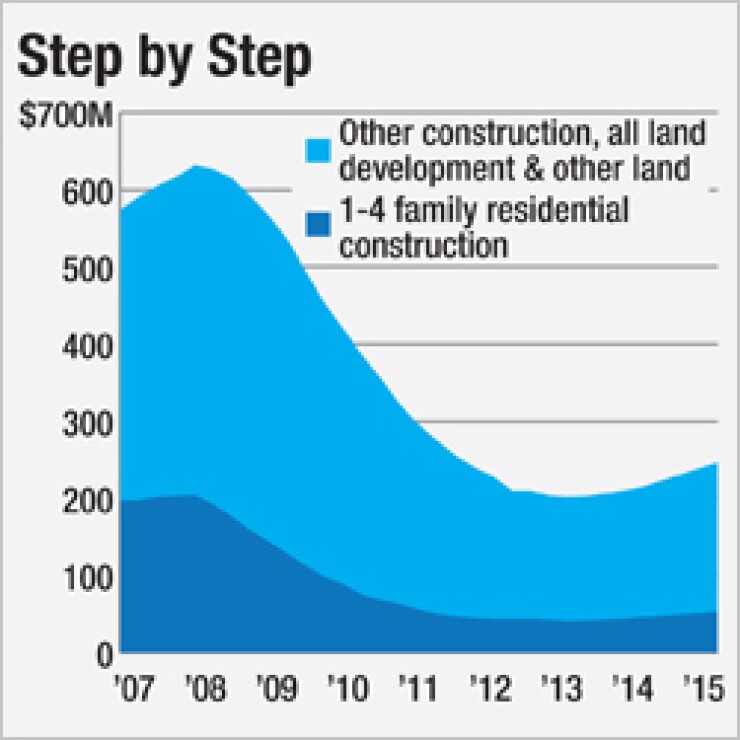

A NAHB analysis of bank call report data shows that outstanding 1-4 unit residential ADC loans rose 4.8%, or $2.4 billion, during the first quarter of 2015. It represents the eighth consecutive quarter of growth. The total stock of residential ADC loans hit $53.6 billion as of March 31, up 31.5% from the first quarter of 2013.

However, that is still 74% below the peak for ADC lending during the first quarter of 2008, and the large and publicly traded builders seem to have greater access to financing than smaller builders.

Most of NAHB's members build less than 20 homes a year and the environment is more challenging for them. Many of the smaller builders defaulted on construction loans during the downturn and still cannot qualify for bank credit.

Signs also point to nonbanks being more active in the market than during the boom. They include private equity firms and boutique lenders that only focus on certain geographic area. Yet the nonbank lenders typically focus only on construction loans, as opposed to acquisition and development.

"From our surveys, we see almost twice as much money coming from non-banking sources to fund AD&C today as was the case in 2005-2008," Ledford said.

But making good construction loans is still tough in the new market.

The most attractive lots tend to be in urban areas, where the larger banks are focusing their efforts. Hill said Regions is concentrating on the inner parts of metropolitan areas like Atlanta, Dallas, Raleigh, N.C., Charleston, S.C., and St. Louis, where buyers want to live. But there are not a lot of remaining lots for development in those areas, making competition fierce. By contrast, there is a surplus of available lots on the outskirts of metropolitan areas. "The lion's share of [remaining] lots is in the exurbs," Hill said, but "most of those lots won't be developed for quite some time if ever."

Meanwhile, the larger regional banks are also facing competition from smaller institutions.

The community banks are "pretty aggressive and they have a lot of loan officers that came from larger banks in the aftermath of the downturn," Hill said.

Jack Hartings, president of The Peoples Bank Co., a $445 million-asset institution in Coldwater, Ohio, said he started to see homebuilding come back in the bank's region in the summer of 2013 as the local agricultural economy grew.

The bank has focused on making construction loans directly to the buyer, as opposed to the builder. Customers will typically buy a lot in a subdivision and hire a contractor to build the home. They typically have a lot of equity already in their current home.

Compared with the housing boom, "today we are seeing a higher quality of borrower with a greater down payment," said Hartings, who is the chairman of the Independent Community Bankers of America.

Most banks use their commercial real estate division to make construction loans, but others have taken a different approach.

For example, the $902 million-asset Bank of Utah in Ogden makes construction loans to homebuyers through its residential mortgage unit, where specialists are trained to understand Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac guidelines for a 30-year fixed-rate loan. While a CRE loan officer might look at a six-month construction loan as a good deal, "they are not focused on the long portion of it," said Eric DeFries, a vice president at the bank.

That approach served the bank well before and after the crash. "We were active in this market through the downturn and saw a lot of our competitors go under," he said.