Foreclosures and delinquencies may seem like problems from the past, but servicers are still struggling with a massive backlog of distressed loans and a return to normalcy is at least two years away, if not longer.

Large banks that had their reputations tarnished by the foreclosure crisis continue to

Stepping in are special servicers and a growing group of mortgage bankers trying to adapt to ever-changing regulations. These servicers are hyper-focused on complying with regulations and maintaining relationships with borrowers.

"In the new normal, servicing is all about compliance," said Jim Madsen, an executive vice president of loan administration at Guild Mortgage, a San Diego servicer of 95,000 loans with an unpaid balance of $16 billion. "My best friend is my compliance officer."

Here are five major areas of concern for servicers right now.

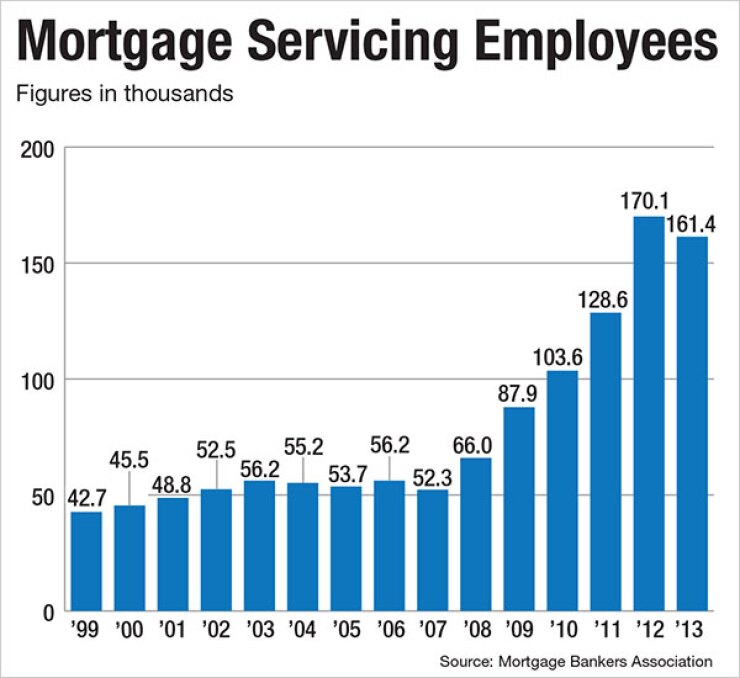

Layoffs a Sign of the Times

The largest mortgage servicers — Wells Fargo, JPMorgan Chase and Bank of America — have laid off thousands of employees at their servicing units in the past year as foreclosure and defaults have plummeted to new lows.

The layoffs are a natural result of large banks selling off mortgage servicing rights, mostly to nondepositories, and whittling down distressed assets.

Bank of America has cut 11,700 employees since the fourth quarter of 2013, an 8% drop in the number of employees at its legacy assets and servicing division. At its peak, that unit had 59,000 workers dealing with loans originated mostly by Countrywide, which B of A purchased in 2008.

JPMorgan Chase has cut 7,500 mortgage employees in the past year, most of them in servicing. Wells would not disclose layoffs or its employee headcount, but confirmed it has adjusted its staff because of the substantial improvement in delinquency and foreclosure rates related to the economic recovery.

In sharp contrast, Nationstar, the Lewisville, Texas, nonbank and fourth-largest servicer, has laid off just 100 servicing employees in the same period. Meanwhile, smaller special servicers are hiring. That difference underscores the dichotomy between banks, which still

"Default staffs have gone down but compliance, procurement and risk management staffs have grown," said John Vella, chief revenue officer at Altisource Portfolio Solutions, a Luxembourg-based spinoff of Ocwen Financial, that owns the mortgage cooperative Lenders One and Equator, a maker of default servicing software. "Everyone is facing scrutiny."

Turmoil for Nonbanks and Loan Transfers

Though Ocwen Financial has captured the headlines of late for

The monitoring committee of state attorneys general, which was formed to enforce the National Mortgage Settlement, is

Incorporating a servicing portfolio into legacy systems remains a big challenge. Regulators are clamping down on issues that directly affect borrowers such as so-called "in-flight mods," whereby a borrower gets a modification from one servicer even as the loan is being transferred to another.

In that sense, the mortgage crisis isn't over at all. Distressed loans have simply been transferred from banks to nonbanks, or moved from one special servicer to another.

There still remains a huge backlog of delinquent loans and loans in the process of foreclosure that banks have to work through, with more servicing transfers to come.

Banks currently have $57.9 billion residential loans in the process of foreclosure, according to Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. filings compiled by BankRegData.com. That represents just 48% of all nonperforming loans.

"The backlog is still huge and substantial. Nobody is done," said Andy Laing, chief operating officer at Fay Servicing, a Chicago special servicer of 25,000 loans carrying an unpaid balance of $6 billion. "We thought this wave might come to an end by 2016, but given the supply out there, it's at the very least a couple of years."

Transferring loans with the right data, documents and borrower contact information is still a huge challenge for the industry.

"When you start transferring loans around, a few documents are going to get lost, and that's never been a strong suit for the industry," said Madsen, at Guild.

David Biderman, a partner at the law firm Perkins Coie, which represents nonbank servicers, said litigation is still on the rise.

"The big banks have been warehousing these loans, they haven't been servicing them, so the transfer of servicing rights is going to continue to promote litigation," Biderman said.

The Incredibly High Cost of Servicing

There is an ongoing debate about whether the industry standard 25-basis-point servicing fee accurately reflect the true cost to service.

Some servicers have proposed raising that fee while others favor a "fee-for-service" model where the base fee would be reduced, but servicers would be paid a la carte for further work.

"We have a conversation on a daily basis about cost," said Laing. "We walk away from a lot of business because we can't do it for a certain price. If you want to take folks out of foreclosure, you have to provide more intense service, and it's going to cost more than 25 basis points."

For nonperforming loans, the goal is to get the borrower into a modification so the loan can become current, but doing so requires intense borrower dealings, which increases the cost.

"You almost have to be a national lender to create enough volume to justify the cost," said Kevin Osuna, senior vice president of mortgage servicing at Gateway Mortgage, a Tulsa, Okla., servicer of 35,000 loans with an unpaid balance of $5.5 billion.

Lenders Keeping — or Selling — Servicing

Though mortgage banks historically only originated loans and then sold them off to aggregators, the rapid run-up in values for servicing rights has made servicing a valuable asset worth holding — and

MSRs rise in value as interest rates climb, largely because borrowers aren't refinancing, so fewer loans are paying off. The income stream also offsets lower margins from purchase loans.

The influx of mortgage banks retaining MSRs has changed some dynamics. Many are originating, but then selling off, niche products like jumbos or adjustable-rate mortgages that are harder to fund. Since newer loans have much higher underwriting standards, hedge funds, private equity investors and banks are snapping them up.

"It used to be buyers didn't want deals below $1 billion, but now buyers are taking what they can get in smaller deals and are lowering their required yield to win the bids," said Dave Stephens, the COO and CFO of United Capital Markets, an advisory firm in Greenwood Village, Colo.

More Regulations Could Lead to Consolidation

The rapid growth of both nonbanks and mortgage bankers as servicers has caused regulators to ratchet up liquidity requirements. The concern is that smaller and regional nonbank servicers might not have adequate access to capital if the economy sours and they are hit with waves of defaults.

Servicers are still digesting the impact of a proposal by the Federal Housing Finance Agency, requiring that nonbank mortgage firms meet minimum liquidity and net worth standards. The proposal also requires that firms maintain more capital against non-agency servicing assets.

The proposal could make it tougher for smaller mortgage firms to survive.

"The banks are being squeezed from the top through Basel III and now they're squeezing independents on the small side, so I would not be surprised if there isn't some regional consolidation to conserve costs and leverage combined compliance," said Osuna. "It's going to be harder and harder for smaller guys to continue to be able to survive with the overall cost structure."