When Lori Noble became an apprentice home appraiser in 1995, she felt she'd found her calling.

It was analytical but allowed her to work outside. She could own her own business and serve her community in southern West Virginia. The opportunity for growth seemed almost limitless. Until it wasn't.

"I really thought that I was at the forefront of something new and different, and I just found every move that I made, I got squashed," Noble said. "There was no opportunity. I guess if you live in a big city or something like that, but not for any rural or underserved provider. There's not a lot of opportunity. You have to make it yourself and that's what I was ready to do, but they take that away from you."

Today, Noble's enthusiasm for the appraiser profession has turned bitter. Her issues lie with her state's licensing board — which she said has needlessly stifled her career on multiple occasions — and the federal regulators that did nothing about it. And she's not the only appraiser who feels that way.

The field is too difficult to get into, too easy to get booted out of and too bogged down with bureaucracy, appraisers around the country say. The ranks of appraisers are too old, too white and too male. And for banks and other lenders, especially those in rural communities, there aren't enough appraisers to keep up with demand.

Then there's the issue of racial and anti-minority bias. A deluge of research data and press-reported anecdotes about Black and Hispanic homeowners routinely having their homes assessed below market value has put real estate appraisal in the Biden administration's crosshairs as it looks to root out institutional contributors to racial inequality.

The problems are numerous and there is ample blame to be spread around. Many in the field point fingers at The Appraisal Foundation, a nonprofit industry group with congressional authority to write the rules on appraisal licensure and best practices.

The foundation has been called a monarchy by those who say it has unlimited power over appraisers and a monopoly by those who are critical of the way it uses its copyright on the Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice, or USPAP, to finance its operations.

Yet, by all accounts, it is acting in accordance with the law. The foundation was given national rulemaking authority by the 1989 Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery, and Enforcement Act, or FIRREA — one of several pieces of legislation passed in the wake of the savings and loan crisis — a law that intended for the Foundation to be a wholly independent entity, which would ensure appraisers were an effective safeguard on malfeasance by mortgage lenders and borrowers.

In practice, FIRREA has given the foundation tremendous power over the nation's more than 78,000 property appraisers and its 55 state and territorial licensing boards, which are required to implement its standards. But neither the law, nor Congress nor those implementing agencies have much power to challenge the foundation's decisions.

"Over about 30 years of appraisal licensing, the Appraisal Foundation has learned to exploit all of the benefits that were written into FIRREA and into Dodd-Frank," said Jeremy Bagott, a California-based appraiser. "It's essentially a publisher and it has a captive audience."

Tweaks and tucks

There are serious challenges in the field of property appraisal. Inflated or phony appraisals were contributing factors to the growth of the mortgage bubble that popped in 2008. But even the foundation's critics do not accuse it of being idle in the face of those challenges.

On the contrary, the organization's rulemaking boards are highly active, at one point making changes to USPAP after every quarterly meeting. They have gradually made their updates annual and finally biannual, but each update allows the foundation to print a new standards handbook and amend its mandatory training courses.

But many iterations of training manuals in itself is not a solution; indeed, critics say the numerous revisions have been counterproductive. Often the changes have been minor, with only a few words altered from one edition to the next. Sometimes new concepts have been introduced in one update, only to be stricken from the next, leading some appraisers to feel like changes were being made simply for sake of change.

"There were some times where — and this is going to happen sometimes — where the board changes a definition, and then it's out in the marketplace, and we realize, you know what, we were probably better off with the previous one," Dave Bunton, president of the Appraisal Foundation, explained.

Bunton said USPAP is a living document and it is his organization's duty to keep it up to date with all the most recent developments in the profession. But he has heard the profession's concerns about "tweak and tuck" amendments and has promised to the organization would "try to stay away from the dotting of the i's and crossing of t's kind of stuff."

Bunton noted that the next edition of USPAP will not be pegged to a set effective time frame, but instead will only have an effective start date, a change that he says could enable the foundation's boards to change rules less frequently.

"In a dynamic marketplace, maybe nothing will happen for 36 months, maybe a lot will," Bunton said. "We're going to say it's effective until we believe there is enough need to change it, and maybe that'll be three, four or five years."

Such a change is a significant departure from the organization's status quo, said Jim Park, director of the Appraisal Subcommittee, an arm of the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council.

Park said the foundation would frequently begin the process of publicly evaluating the next round of changes just months after publishing a new set, a practice that has been highly disruptive to the profession as appraisers are left to question which rules are going to last from one publishing cycle to the next.

"It creates a situation where the profession is constantly in turmoil in terms of what the standards really are," said Park, who is also a certified general appraiser in Virginia. "That makes it difficult for state regulators investigating complaints. It makes it difficult for lenders who have to ensure that the appraisals that they're receiving are in compliance with USPAP."

Last year, the Appraisal Subcommittee commissioned a study of the Appraisal Foundation's rulemaking activity. It found that the foundation had made more than 3,600 changes to its standards and advice over the years, but many of them had "no practical impact on the appraisal practice," Park said. Instead, they have created an atmosphere of uncertainty that has kept appraisers from addressing some of the more pressing issues facing the industry.

"Instead of being able to focus more on how we advance the profession, advance appraisal practice, using more technology, using better data sources, really moving the profession forward, the profession is constantly enthralled with 'What's the next change to USPAP?' " Park said. "It would be nice to get some standardization of the standards for a period of time so that appraisers, educators and others could focus on how we advance the profession in other ways."

Perpetuating error

Beyond annoyance and confusion, many of the standards set by the foundation don't meet the process standards that most regulatory bodies are bound to. Ted Whitmer, a Texas-based appraiser and attorney, said that can be even more damaging for the profession.

"It fails as a legal document," Whitmer said of USPAP. "It doesn't have specificity. It's too open to interpretation. Not all of them, there are some standards that I call the black-and-white standards, but there's a lot of undefined terms in USPAP."

Whitmer has been on all sides of the appraisal regulatory ecosystem. He has been a member of the Texas Appraiser Licensing & Certification Board. He has also defended other appraisers in front of that same board and served as an expert witness in disciplinary hearings and court cases around the country.

Whitmer said USPAP works well as a guiding document from a professional organization because it is flexible enough to be applied to a variety of circumstances in the field. But when adopted, as is by state boards, that flexibility can be used against appraisers.

In circumstances when a standard or definition is in question, deference is given to the regulatory body's interpretation, Whitmer said. To make matters worse, in instances when regulators hand down discipline based on flawed interpretations, they have an incentive to continue following that interpretation in future cases. If they don't, they risk opening themselves up to litigation.

"You've got a regulatory climate that is perpetuating error — and it has to, constitutionally," Whitmer said. "That's the problem. One of the problems, I should say."

Sometimes these wrong interpretations are exposed in court, Whitmer said, but in these instances, boards have been known to drop cases rather than carry through to a decision to avoid codifying their mistake. This spares the appraiser their license but can be extremely costly. Not all appraisers have the resources to fight such battles.

Noble agreed to consent orders on both of her reprimands from the West Virginia Real Estate Appraiser Licensing and Certification Board despite what she said are dubious circumstances around the events.

The first incident involved a misstatement of value on a conservation easement. She said the document in question was merely a draft appraisal that was never finished because her supervisor fell ill.

The second, she said, should have been a civil suit rather than a licensing matter. A client claimed Noble did not complete an appraisal after accepting a fee. Noble maintains she finished the report and it was lost in the mail.

The marks against her have made it difficult to get anything but the most basic residential appraising assignments.

"My name is on every blacklist in the country, even though I'm a very good appraiser," Noble said. "Because of that, I could never compete. … It squashed my ability to generate revenue, take care of my family, everything."

'Sweeping authority'

Last year, President Biden convened the Property Appraisal and Valuation Equity task force, an interagency group commissioned to explore issues of bias in the residential valuation process.

The group, led by Housing and Urban Development Secretary Marcia Fudge and Director of the Domestic Policy Council Susan Rice, has called for a litany of changes to how appraisals are trained, how appraisals are conducted in the field and how the profession is supervised.

Park, who is also part of the task force, would like to see an overhaul of the appraisal regulatory system to make it more like other regulated professions.

"In our research, we have not found any other regulatory system similar to the present regulatory system," he said. "I'm not aware of any other private authority out there that has the kind of sweeping authority the foundation has."

The Appraisal Subcommittee and the Appraisal Foundation worked to regulate the appraisal industry together in relative harmony for roughly 30 years. The Foundation wrote the rules for the state boards and the Subcommittee made sure the boards adhered to them and enforced standards for federally regulated transactions. But since 2020, the relationship between the two organizations has been tenuous.

The Appraisal Subcommittee was also born out of FIRREA. Composed of representatives from HUD, the Federal Housing Finance Agency, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, the Federal Reserve Board, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency and the National Credit Union Administration, the subcommittee has enforcement authorities over state licensing boards. When it comes to the foundation, the subcommittee's powers are limited to oversight.

At best, the subcommittee had "the power of the purse" or "moral persuasion" over the foundation, Park said, by virtue of an annual grant it provided to support the Appraisal Standards Board and the Appraisal Qualifications Board. However, neither side could recall the subcommittee attempting to use its funding to exert influence over the foundation.

"We were a grant recipient for 30 years and I can never remember one instance where there was this quid pro quo, 'If you don't do this, we're going to take your money.' Never," Bunton said. "It was always a partnership. Just in the last two to three years, all of a sudden, particularly the ASC staff, has gotten more adversarial."

The dynamics seem to have shifted in 2020 amid an overhaul of the subcommittee's grant policies. The subcommittee's newly hired grant director recognized that the foundation's proceeds from selling USPAP handbooks exceed the cost of developing them, in part because that development process is subsidized by the Subcommittee's grants. Those proceeds constitute program income — income that, in the world of federal grants, frequently comes with strings attached, including documentation and reporting requirements.

"It became clear to the foundation and to the subcommittee that the money that was thrown off from the grant resulted in program income and that program income was subject to oversight to a degree by the subcommittee," Park said.

This was too much for the foundation. In August 2020, Bunton wrote a letter to Park formally declining the subcommittee's $350,000 grant for that year, noting that the foundation had realized significant cost savings because of events that it had canceled because of COVID-19. He said the funds should be dispersed to state appraisal programs instead.

The foundation has declined subcommittee funding for the past two years as well. Bunton said the process had simply become too complicated.

"It was much more micromanaging and much more labor intensive, a lot of the paperwork, surveys we had to fill out and everything else," Bunton said. "It was kind of like, you know what, it's just not worth it."

The Appraisal Foundation's budget seems not to have suffered from the loss. In 2020. The foundation generated nearly $5.3 million in revenue, according to Form 990 filings published by the nonprofit news organization ProPublica. Financial independence is one of Bunton's crowning achievements since taking the helm at the foundation in 1990, he said.

Bunton, who earned a salary of $375,614 in 2020, according to ProPublica, is a graduate of Harvard's Kennedy School of Government. He spent a dozen years as a staffer on Capitol Hill and two as vice president of the Federal Asset Disposition Association before finding his home at the Appraisal Foundation.

During the past 32 years, Bunton and the organization have become synonymous with one another. Under his leadership, the foundation has brought uniformity to a highly dispersed profession mostly made of independent practitioners. He says he has testified in front of Congress on behalf of the appraisal profession at least seven times since 1995, including appearances in 2016, 2019 and this year.

Bunton has also expanded the organization's reach globally, leading envoys abroad, hosting foreign delegations and forging international alliances.

"Our organization has made a significant difference," he said. "All 50 states and five territories all use the same exam. It's a very competitive exam. You know, we have meaningful qualifications that aren't onerous. … We still have a lot of way to go, but I think, all in all, it's been pretty good."

A lack of diversity

If the foundation has been diligent in updating its rules, it seems to have been less diligent in addressing the lack of diversity in the appraisal industry.

Many industries are grappling with inclusion, but real estate valuation is one of the least diverse professions in the country. Nearly 98% of appraisers are white and almost 70% are male, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Such a lack of diversity has only made the profession more susceptible to attacks from politicians and civil rights groups that say its members discriminate against people of color.

Earlier this year, the PAVE task force put out a report noting that homes in majority Black or Hispanic neighborhoods were roughly twice as likely to be undervalued compared to their contract prices than those in white neighborhoods. It also found instances of appraisers describing area demographics in their valuation reports.

The task force's revelations followed a string of media reports about Black homeowners who have dealt with discrimination from appraisers. Some even

Individual appraisers have argued that discrimination is not the norm and that valuation discrepancies are more often a function of deep-seated market realities than proof of bias. But the profession's history and homogeneity have given those claims little credence.

"Some may say that the words of one appraiser do not reflect or represent the profession," Rep. Maxine Waters, D-Calif., wrote in a letter in February to the Appraisal Foundation, the Appraisal Subcommittee and HUD. "However, years of data, ongoing research, and numerous settled lawsuits provide ample evidence to the contrary."

Jonathan Miller, a New York-based appraiser, said bad actors and the lack of diversity both hurt the credibility of appraisals across the country. He blames the Appraisal Foundation for failing to address the issues.

"Whether appraisers are racist or not or there's some element of that, is not ruled out by the physical composition of the industry," he said. "There's a shortage [of appraisers] but there probably wouldn't be if there wasn't some sort of implicit bias that the foundation has created to prevent the industry from being represented by everybody."

Bunton said he has noticed the lack of diversity among the ranks of appraisers over the years, but instances of bias have only recently arisen as primary concern for the profession.

"Appraisal or valuation bias, three or four years ago, if I heard that mentioned once every year or two it would be a lot," he said. "It's a huge issue now."

Bunton described recent reports of blatant bias by appraisers as "unbelievably disturbing." He said the foundation is amending its ethics rules to make it clear that discrimination will not be tolerated. The Foundation hired a fair housing law firm to advise on the process.

Park said these types of issues might have been addressed already had the Appraisal Foundation, like most regulatory bodies, been subject to the Administrative Procedure Act. Agencies subject to the APA must create rules with specific notice-and-comment periods that receive input from a wide swath of interested stakeholders. APA rules typically apply to federal regulatory agencies.

Instead, the foundation releases exposure drafts that are open to public commentary. "If there's one word I would associate with our organization it's transparency," Bunton said.

But Park said the exposure draft process is much less encompassing than APA rulemaking, as most of the input comes from individuals close to the appraisal industry itself.

"I've been around this for over 20 years, and rarely do they get comments from civil rights, fair housing or advocacy groups," Park said. "It's mostly from people very focused on appraisers."

Few and far between

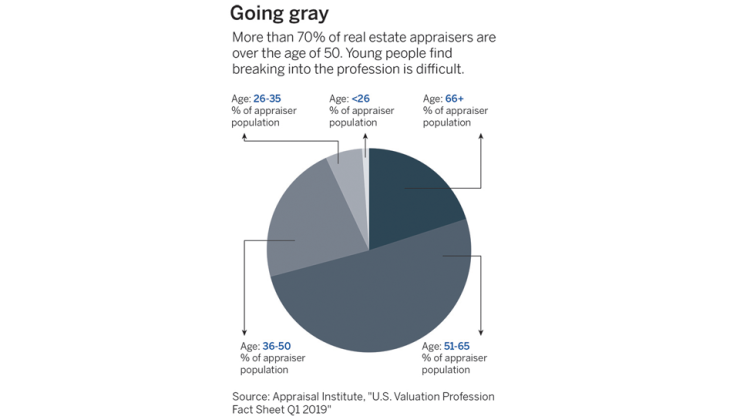

The inability of the appraisal profession to attract diverse workers is part of its larger struggle to attract any new entrants at all. A 2019 report from the Appraisal Institute, a global trade group, found that the ranks of the profession had shrunk 2.6% annually in the U.S. over the prior five years.

In addition to being overwhelmingly white, the profession is also increasingly going gray, with more than 70% of its members over the age of 50, according to the same Appraisal Institute report, including 20% that are older than age 66. As older appraisers retire, there are fewer newcomers to replace them.

The dearth of appraisers is being felt most acutely in rural states. Kentucky, New Mexico and Utah reported statewide shortages in 2018, according to a report from the Conference of State Bank Supervisors. Six other states said they were struggling to fill appraisal requirements in their rural regions. Since 2019, North Dakota's appraisal system has been operating under a waiver on all transactions valued below $1 million.

Bunton said the foundation supports initiatives to help the profession grow and diversify, but ultimately its greatest contribution is making sure its qualifications standards do not limit growth.

"We are putting in a lot of effort into making the profession more diverse, more reflective of the country that we live in, but we're not an advocacy group. We're not a trade association, you know, the Appraisal Institute or the American Society of Appraisers. That's more in their bailiwick," Bunton said. "What we want to make sure is that we don't have any unintentional impediments to people who want to become appraisers."

Yet some in the profession feel the training required to become a licensed appraiser is a limiting factor, for both trainee and mentor alike.

Before being licensed, trainees must complete several educational courses, pass an entry exam and get 2,000 hours of on-the-job training over two years, often with little to no pay because they cannot legally appraise properties. This is a high barrier for many from lower income backgrounds to clear.

Mentors, meanwhile, have little incentive to take on the workload and liability of training someone new. And because of the shortage of appraisers, once a trainee is licensed, they can fairly easily go off on their own or join a bigger firm.

"I used to be real proud of the fact that I helped set up seven different competitive shops in the Richmond metropolitan area, but I'm not so proud of it anymore. I'm pissed off I was that damn stupid," said Pat Turner, a 50-year appraisal veteran in Virginia. "That is a very, very selfish way to look at it, but like I say, I've been taken advantage of seven times. I think that gives me the right to be a little PO'd."

This point of view leads many appraisers to search for successors and trainees who share their interests: their own children and relatives. And in turn, making appraisal a family business only reinforces the difficulties the industry has in attracting new entrants from different backgrounds, observers said.

'I knew it was wrong'

Between the PAVE findings, the internal conflicts and the public attention on home valuations, the appetite for changing appraisal policy is as strong as it has been in decades.

In March, the House Financial Services Committee held a hearing on appraisal bias and the impact on communities of color. During the hearing, Waters, who chairs the committee, introduced a discussion draft of her Fair Appraisal and Inequity Reform, or FAIR, Act, which would replace the Appraisal Foundation and Subcommittee with a new regulatory body known as the Federal Valuation Agency.

The bill would also beef up fair housing training, create a registry of appraisals, track demographic data for home values and establish harsher penalties for discrimination, among other things.

While the Waters proposal would satisfy several interest groups focused on appraisals, it has yet to be formally introduced and has not attracted Republican co-sponsors, meaning it is unlikely to advance through Congress anytime soon, especially with midterm elections rapidly approaching.

Because of this, the window for making serious reforms to the profession may be closing, Miller said, noting that discussions have only come this far because of Democrats' focus on racial equity. Should Republicans take the House or Senate this fall, the issue will likely fade.

"That's what the foundation is counting on, I believe, that they can ride out this pain, this spotlight, they can weather it until the midterms," Miller said. "Hopefully, there'll be some action before then."

Even if the FAIR Act could gain enough traction to pass into law, it would not be a silver bullet for the profession. The problems facing appraisal are myriad and multifaceted, Whitmer said. Some were self-inflicted while others are the result of greater societal woes.

"One of the cognitive biases is that everything is simple and the solution is simple, when in fact there's a lot of complexity at times and simple solutions are not the right answer for complex problems," Whitmer said. "That's what I think we have here."

For Noble, the resolution lies in a rethinking of how occupational licensure works broadly. Too often, she said, regulators are more focused on protecting the status quo than doing what is right. In the valuation space, loosely written laws have allowed state boards to run roughshod over current and would-be appraisers, she said.

Her final encounter with the West Virginia board came last year, as she tried to help her apprentice, Hollie Beckwith, attain her license. It took more than a year after Beckwith submitted her application for her to be rejected. And she never received an explanation as to why. For Noble, this was the last straw.

She went to the Appraisal Subcommittee hoping it could remedy the issue but was told the agency didn't have jurisdiction over licensure standards. Noble was told to contact her governor and local media to raise awareness of the issue.

Instead, she joined other appraisers in the states who had similar issues with the board. Together, they called for a legislative fix. Earlier this year, that effort culminated in a new law in West Virginia requiring the real estate appraiser licensing board to issue decisions on license applications within 15 days, provide specific reasons for rejection and allow the applicant to remedy the issue and reapply.

With the legislation in place, Beckwith was able to obtain her license and now practices in Craigsville, West Virginia.

For Noble, the experience showed her that change was possible. She has now left the appraisal profession to pursue a different career. In July, she took a job with West Virginia University's Knee Center for Occupational Regulation. There, she will study the impact of appraisal regulatory regimes throughout the country.

"I knew it was wrong, and took it to task and that just elevated me to just keep digging further and further," she said. "Now I have the Knee Center behind me, so sky's the limit."

At the federal level, Noble said she feels both the Appraisal Subcommittee and the Appraisal Foundation bear responsibility for the state of the profession. While she understands the subcommittee's limited authority, she believes it could use its oversight role for state boards more effectively.

As for the Appraisal Foundation, she said the organization has done some good for the profession and provided key changes to remedy blatant faults within USPAP. But, ultimately, she said the foundation had ample warning about many of the problems in the industry and chose to do nothing.

"They have had 30 years to correct the heavy burden of this two-year cycle of USPAP and competitors at the regulatory level using USPAP, weaponizing it to take out competition," Noble said. "They've had, to me, in my opinion, at least 20 years to correct that and they never budge. So whatever is coming down on them, they deserve it."