Note: This is part one of a two-part series on the widening gap between average consumer and homebuyer credit scores.

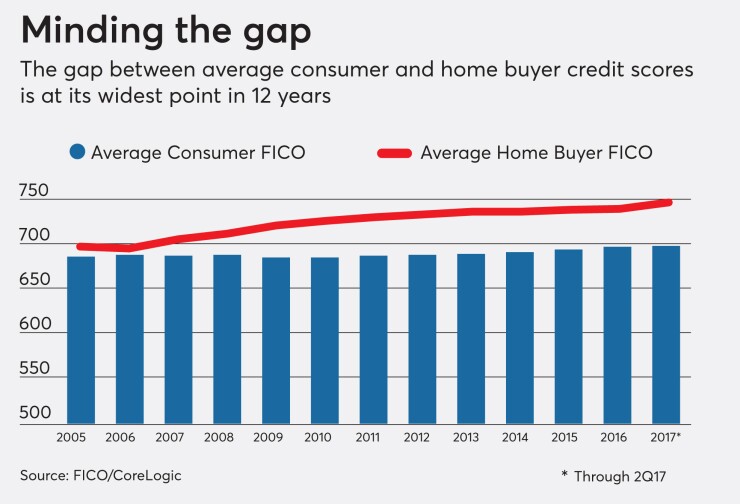

The average U.S. consumer FICO credit score reached 700 for the first time during the second quarter of 2017. At the same time, the average credit score for purchase mortgage borrowers was 745.

That gap between average consumer and homebuyer credit scores has widened significantly and now sits at its highest point in 12 years. In 2005, the national average credit score was 688, only nine points shy of the 697 average score for homebuyers, according to data from FICO and CoreLogic.

There's no single reason why these figures have diverged so much, and whether or not it actually represents a problem for mortgage lenders is a matter of perspective.

The observation is nevertheless noteworthy, given the difficult shift the industry is making to a more

To be sure, the housing crisis stunted consumer appetite for mortgages. But the credit score gap may also indicate that lenders aren't taking on as much risk as they could be, despite new tools and policies that would allow them to responsibly lend to the full limits of the credit boxes of agency and government-guaranteed loan programs.

In addition to using tools like the government-sponsored enterprises' automated data validations and representation and warranty waivers to more safely take advantage of an extended credit box, lenders can also "take the opportunity to look beyond just the credit score, and start to understand credit behaviors and trends of potential borrowers," according to Joe Mellman, senior vice president and mortgage business leader at TransUnion.

Some mortgage professionals also attribute the growing credit score gap to borrowers who have essentially fallen off the map, due primarily to altered consumer behaviors from the Great Recession.

"So many lenders have tightened their underwriting and guidelines in a variety of ways, but the major reason that credit scores have increased is not because of a restriction from lenders," said Sam Khater, deputy chief economist at CoreLogic. "It's the fact that lower credit borrowers have dropped out of the market — lower credit meaning below 640."

Consumer awareness about credit scores and how financial institutions use them to make lending decisions has led to a general improvement in overall scores. But when it comes to mortgage lending, there's still a disconnect between the credit profile that consumers think they need and what lenders actually require to get a mortgage.

Missed payments and increased debt loads are primary drivers of lower credit scores, and they go hand-in-hand with economic downturns, according to Ethan Dornhelm, vice president for scores and analytics at Fair Isaac Corp.

"The FICO score generally will start to go down as the effects of a recession start to play out in the form of increased delinquencies and increased debt, and will start to improve and recover — as we've pretty much seen in the extended recovery since 2011 — as consumers start to get past those payment stressors and start to make payments on time and deleverage."

Meanwhile, stricter underwriting requirements put in place in response to the housing crisis are just one reason the average borrower credit score has gone up.

"The recession was heavily centered in the mortgage space and mortgage credit conditions had been much easier in the bubble period, so credit scores being accepted were much lower," said Doug Duncan, senior vice president and chief economist at Fannie Mae. "But because of the large rise in foreclosures and losses, then mortgage credit tightened, and so the qualifying credit score will have gone up."

Stricter guidelines in lending carry partial blame for the widened gap between the average consumer credit score and the average borrower score, but tighter measures were employed to prevent future losses.

"I think the basic message that came out of Dodd-Frank, and I think the basic lesson that the industry learned was if you're going to make mortgage loans, you better make it to people who have the ability to pay, and I think too that consumers have learned as well. I know a lot of people who were very badly damaged during the economic crisis have learned how to handle credit better," said Ann Fulmer, chief strategy and industry relations manager at FormFree Holdings Corp.

"[T]he major reason that credit scores have increased is not because of a restriction from lenders. It's the fact that lower credit borrowers have dropped out of the market."

— Sam Khater, deputy chief economist, CoreLogic

But along the way, consumer perceptions of a process with much higher standards has dissuaded them from applying.

"Because credit conditions in mortgage tightened, if consumers have weak credit, they simply don't apply, so the average credit score of those who do apply would be higher," said Duncan.

Between the average consumer and homebuyer credit scores, the general population score is more stable.

"The average scores of the mortgage population is a concentrated subsegment of that population and can generally be influenced by two things: the profile of those who are actively seeking mortgages, and that can shift over time and perhaps shift to a higher or lower credit quality population as we move through different economic cycles; and the other side would be the supply side, where lender appetite for levels of credit risk can shift through the cycle, along with a borrower's appetite for credit," said Dornhelm.

In terms of the pool of applicants, older distributions of the population typically have higher scores than younger distributions because they have longer credit histories and more experience managing credit. And since

Gradually though, consumers are starting to perceive that credit standards have eased somewhat, according to Fannie Mae's National Housing Survey, which began tracking consumer sentiment toward lending standards in 2010. It wasn't until 2014 that a majority of consumers surveyed had a positive outlook on lending standards.

Even with this slow progress, consumers haven't been pouring back into the mortgage market.

"No one knows exactly why consumers dropped out. Some of it could be the perception of tighter underwriting, it could be that they don't have the down payment, it could be that they have legacy and scarring from the recession — the one lesson learned from the Great Depression in the '30s and early '40s is that it radically changed the financial behavior and character of people that lived through it. They began to save a lot more, got much more conservative from a financial standpoint," Khater said.