Two years after the U.K. Financial Conduct Authority announced an end date for the London interbank offered rate, there has been an alarming lack of progress in preparing for a conversion to a new benchmark.

For starters, the Secured Overnight Financing Rate — which regulators are touting as an alternative for dollar-denominated assets — is risk-free, and so is unlikely to behave like Libor during periods of market turmoil.

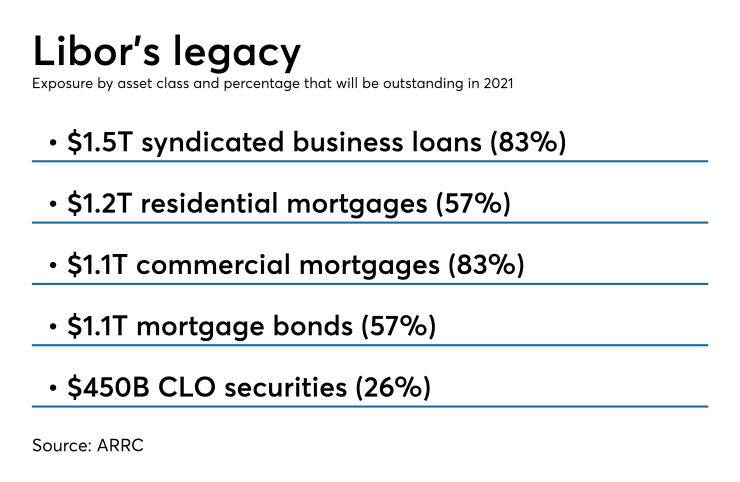

Even if a more suitable benchmark were available, the $1.5 trillion of syndicated corporate loans, $450 million of collateralized loan obligations and $200 billion of mortgage bonds and other asset-backed securities that reference Libor and did not anticipate its demise cannot be switched over without the unanimous consent of investors. That challenge is almost insurmountable, given the difficulty of even

With so much at stake, an industry working group is considering turning to an unlikely source for help: New York's state Legislature. Many of these financial contracts are governed by New York law, the thinking goes, so if there is a dispute in interpretation, the parties to these contracts would look to the laws of New York for direction. Legislation could designate SOFR, or some variation of SOFR, as an acceptable substitute.

Minutes from the Alternative Reference Rates Committee indicate that this was discussed as early as October. And David Bowman, special adviser to the Federal Reserve Board, floated the idea at the Structured Finance Industry Group’s conference in February. He said that before approaching the New York Legislature, the ARRC — a group of industry participants and other experts convened by the Fed in 2014 — would need to make sure that the legal argument is sound and that there is broad support in the financial industry.

There is ample legal precedent for legislation that impairs a private contract, so long as it advances a public purpose. Still, legal experts say that any legislation the ARRC might seek is almost certain to be challenged, if only because choosing an alternative to Libor will inevitably favor one party in a transaction over another.

There is another concern, too: the potential political fallout if legislating a switch to a particular benchmark is characterized as another kind of bank bailout — something that would benefit financial institutions and large investors at the expense of consumers.

“The fact that a legislative solution is even being considered demonstrates that the people closest to it are increasingly desperate,” said Rick Jones, a partner at the law firm Dechert and co-chair of its global finance and real estate practice groups.

“This is all getting considered by people [central bankers and treasury officials] to whom complex legal documents are an everyday occurrence, but it’s got to be understood, implemented, and executed by tens of thousands of people on millions of transactions for trillions of dollars,” Jones said. “That’s scary.”

A legislative solution “would put a stake in the ground and say, 'Everyone pay attention!’ ” he said.

While the ARRC has not yet decided to pursue legislation, and it is unclear what exactly this legislation might look like if it did, here are some preliminary thoughts on what New York lawmakers might, and might not, be able to accomplish.

The narrower the better

The United States Constitution prohibits a state from passing any law “impairing the obligation of contracts.” This clause was written in response to debtor relief statutes passed by many states after the Revolutionary War, which made it unattractive to extend credit, undermining confidence in the economy. Over the years, the courts have carved out a number of exceptions to the clause, notably during the New Deal, but there has to be a strong public policy goal.

For example, in January 1934 the Supreme Court, in Home Building & Loan Assoc. v. Blaisdell, upheld a Minnesota statute temporarily extending the time available for borrowers to redeem their mortgage from foreclosure. Chief Justice Hughes said the state’s exercise of power was justified in order to stave off a catastrophic collapse of the mortgage market.

However, just four months later, in May 1934, the court struck down an Arkansas statute for violating the contract clause in a case considered to limit, or conflict with, Blaisdell. In W.B. Worthen Co. v. Thomas, the owners of a harness company fell behind on rental payments and their landlord gained a judgment against them; one of the tenants subsequently died, leaving his wife with a life insurance payout. When the landlord tried to garnish this payout, the Arkansas Legislature passed a law exempting from process of attachment any proceeds of a life or accident insurance policy.

“Generally, the courts are tolerant of state legislation that has a retroactive effect on contracts where the legislation is not overbroad and advances a legitimate public purpose,” said Howard Altarescu, a partner at the law firm Orrick. “The determination is very fact-specific; the narrower the scope of the legislation, the more likely it is to be upheld.”

So legislation that is very broad and covers contracts that already provide for a fallback if Libor is unavailable would be more problematic than legislation that only covers contracts that do not provide for a fallback benchmark.

Still, litigation is possible no matter how narrowly the legislation is drafted. “A lot of contracts say, ‘Here’s the fallback, but if it’s not available, just revert to last Libor rate published,’ which would change the security into a fixed-rate instrument,” said Andrew Morris, another partner at the firm. “If you’re a borrower in rising-rate environment, maybe you’re happy" with a fixed rate of interest.

It might make sense to wait

The fact that SOFR is a risk-free rate is not its only drawback as a benchmark. For now, at least, it is only available as an overnight rate. That means it does not provide borrowers (or lenders) with certainty as to what their interest expense (or income) will be over a given period.

The ARRC is developing a methodology for a robust term alternative to Libor, but it will be unavailable until the first half of next year at the earliest. This raises the question: Why ask the New York Legislature to specify a benchmark as an appropriate alternative to Libor now when a more appropriate alternative may be available in the near future?

In a February publication, the law firm Arnold & Porter outlined three of the methodologies being discussed. The first is a forward-looking rate based on derivatives of the overnight rate; the second is a "compounded setting in advance" rate based on SOFR over a specified number of days prior to the beginning of the contemplated interest period; the third is a "compounded setting in arrears" rate that is also based on SOFR over a specified number of days, but would be calculated before the end of the contemplated interest period.

There is also discussion about providing adjustment for the second and third options that would to better reflect credit risk.

So while using legislation to overcome the difficulty of identifying all of the counterparties in transactions referencing Libor “may prove to be appropriate,” says Charles Landgraf, senior counsel at Arnold & Porter. “I suspect as a broad-based solution to this multitrillion-dollar problem, it may need to wait until the development of a term rate.”

CFPB may need to weigh in on consumer assets

While most commercial contracts are governed by New York law, many consumer contracts are not. So even if New York lawmakers can be enlisted to smooth the transition to a new benchmark, the legislation would not apply to adjustable-rate mortgages, student loans and other kinds of floating-rate consumer loans made in other jurisdictions.

It is certainly possible that if New York passed such legislation, other states would follow suit. But switching benchmarks on consumer loans is particularly problematic, because lenders face legal challenges and reputational risk if borrowers perceive their rates to be higher than they might have been if benchmarked to Libor. In fact, lenders and servicers have said they are wary of making any decisions about replacing the benchmark on outstanding loans until the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau

And some observers believe that any new rate or margin mechanism applied to consumer loans may need to be lower than the current ones, which of course could erode the margins of lenders and investors in bonds backed by these assets.

"Special care needs to be taken" if a legislative fix "is applied to any consumer product," said Sairah Burki, a senior director and head of ABS policy at the Structured Finance Industry Group. She said that some industry participants are starting to think about looping in consumer organizations. The ARRC is also pulling in a lot of different consumer groups.

There could be a mismatch between assets and liabilities

Switching benchmarks could have implications for the credit ratings of CLOs, mortgage bonds and asset-backeds — though this is true whether or not the ARRC enlists the help of the New York Legislature. The risk is that the loans used as collateral for these securities do not switch benchmarks at the same time, or switch to a different benchmark. Under certain circumstances, this could reduce the amount of funds available to pay interest on the securities.

“Whenever the income of the asset decreases while liabilities payment is not decreasing, or is even increasing, the mismatch becomes more problematic,” said Andreas Wilgen, group credit officer at Fitch Ratings.

The impact on a transaction’s rating will depend on a number of factors, including the timing of the benchmark replacements, the protections built in to the transactions and the remaining weighted average life of the transaction after 2021.

In a recent report, Fitch said that it expects the direct impact on its global portfolio of securitization ratings to be “generally limited in number and scale” as most asset classes are resilient to basis risk stresses.

Wilgen said that of all asset classes with meaningful amounts of Libor-based assets and liabilities, CLO ratings are likely to be the most resilient. That is because leveraged loans can be tied to one of four different rates, ranging from one-month to six-month Libor. What is more, corporate borrowers typically have the ability to switch from one Libor rate to another from month to month.

However, other asset classes could see a larger rating impact if potential mismatches are not adequately addressed, or see erosion of ratings “headroom,” which could contribute to ratings migration in the event of performance deterioration.

No relief from taxes, FATCA

Switching benchmarks can also have tax implications for financial assets, and these consequences are not necessarily limited to the recognition of income. More important, they could include the loss of a securitization trust’s special tax status and the collapse of the transaction.

This is something else that legislation cannot fix.

The New York Legislature saying that switching benchmarks will not be deemed to be a modification “may not pass muster with the Internal Revenue Service,” Landgraf said.

The Structured Finance Industry Group is concerned that uncertainty about the tax consequences may delay the modifications necessary for an orderly transition from Libor, or even stop participants from making them. So it is asking the Treasury Department and the IRS for relief. In a March 28 letter, Burki suggested that the agencies do this in the form of a notice, rather than a regulation or more formal pronouncement. This notice could simply state that a change from a Libor index to an alternative index would not be treated as a taxable exchange.

The Structured Finance Industry Group would also like the agencies to clarify that switching to a new benchmark would not adversely affect deals structured as real estate mortgage investment conduits, or REMICs, by causing regular interest to be treated as not having fixed terms on the REMIC’s startup day.

To add insult to injury, switching benchmarks could also cause a debt instrument that is otherwise grandfathered from the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act, or FATCA, to lose that status, according to the Structured Finance Industry Group. Securitizations domiciled offshore fall under FATCA's umbrella, but because the regulation was not contemplated when many older asset-backeds were issued, their legal structures leave then unable to comply with the reporting requirements. Unless grandfathered, they could be subject to a withholding tax on loan interest, principal payments and sale proceeds.