LOS ANGELES — California has lost two rounds of a lawsuit brought by plaintiffs who say the state improperly diverted money intended for homeowners to make payments on housing bonds.

The administration of Gov. Jerry Brown and state lawmakers want the state's Supreme Court to reverse lower court rulings that found the state wrongly used money from a national settlement with major banks accused of predatory foreclosures to pay debt service on the bonds.

The National Asian American Coalition and two other associations representing home owners brought the case in 2014 naming as defendants Brown; Michael Cohen, who was then director of the Department of Finance; and State Controller Betty Yee.

The Coalition scored a partial victory in Sacramento District Court and won on appeal. The Third District Court of Appeal in Sacramento ordered the state in July to use the money to help homeowners who had experienced foreclosures.

The money “was unlawfully diverted from a special fund in contravention of the purposes for which that special fund was established,” Justice Andrea Hoch said

The appellate court remanded the case to the trial court with directions to issue a writ of mandate directing the state to retransfer $331 million from the General Fund to the National Mortgage Settlement Deposit Fund.

The state government has appealed to the California Supreme Court. Attorneys representing the state are scheduled to file a brief asking the Supreme Court to review the case on Oct. 8.

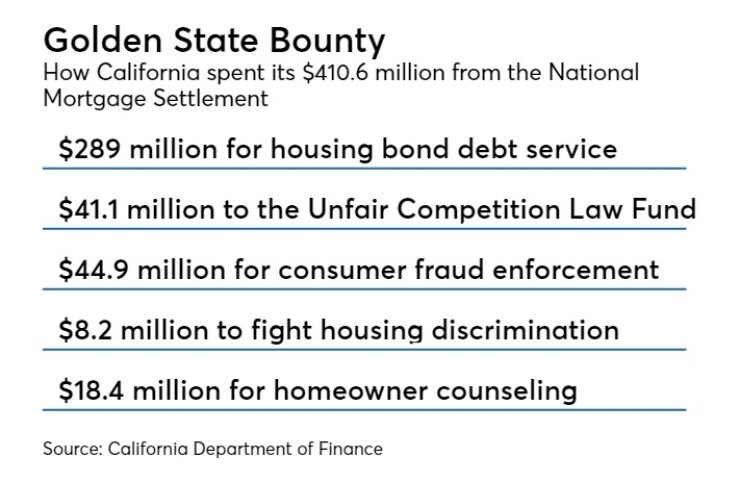

The case is a battle over how California spent $410 million it received in 2012 as part of a nationwide settlement over alleged violations of federal law with the nation’s largest mortgage servicers: Ally, Bank of America, Citigroup, J.P. Morgan Chase and Wells Fargo.

Brown in his state budgets allocated $410 million of the discretionary money to pay state agencies in housing and other programs to cover deficits.

About $298 million was used to offset General Fund costs for housing bond debt service for those programs funded with voter approved Proposition 46 and Proposition 1C state general obligation housing bonds.

H.D. Palmer, a spokesman for the Department of Finance, said the settlement involved two pots of money.

One pot provided $20 billion in financial relief for homeowners all over the country who were harmed by the mortgage crisis, according to court documents. The settlement also provided $2.5 billion to state governments; California's $410 million share -- used to make housing bond payments and pay for other housing-related general fund budget items -- was “discretionary” money in the settlement that states could use as they wished, Palmer said.

Other states put the discretionary money directly into their general funds to use at a later date, Palmer said.

California, on the other hand, proposed and the Legislature adopted, a plan to use the majority of the money to pay down housing bonds — a use of funds that had a relationship to housing, Palmer said.

“This reminds me of the national tobacco settlement,” Moorlach said. “All of these states got all this money for tobacco education — and (former) Gov. Gray Davis used the money, not to backfill Medi-Cal or the Department of Healthcare Services, but used it for the annual deficit and securitized the darn thing.”

According to Moorlach, Michael Moore, the Mississippi attorney general who led the charge against the tobacco industry later said the money from the 1998 Master Settlement Agreement with tobacco companies was not used for the purposes for which it was intended: education about the harms of tobacco and to pay for medical costs associated with tobacco use.

Moorlach said Brown and the Legislature’s response was to say to the court, “we can do what we want with the money.”

Attorneys representing the Legislature raised concerns

"The Court of Appeal reasoned that transferring money from the general fund to the NMSDF did not require an appropriation, because money that had been unlawfully taken out of the NMSDF was, as a matter of law, still in the NMSDF," wrote Jessica Kenny, deputy legislative counsel, in the brief. "The actual effect of the order, however, is to direct the Legislature to draw money from the General Fund for the purpose of making expenditures approved by the Court of Appeal. As such, the order is essentially a judicial appropriation in violation of the separation of powers doctrine and the Legislature's exclusive authority over appropriations."

The court should "clarify that the courts do not have the authority to order the Legislature to make an appropriation from the State Treasury," Kenny wrote.

If the ruling stands, it would result in the "judicial branch usurping the power of the legislative branch," Palmer said. "If it stands, it means the state courts can come in and tell the Legislature how to and where to spend money."