Bank CEO's fire-and-rehire maneuver reaps windfall at taxpayer expense

A multimillion-dollar deal between Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel and Stephen Calk was supposed to deliver 400 new jobs to the city. Here’s what really happened.

By Kevin Wack

Three months before the 2016 election, the chief executive of a small, privately held bank in Chicago was appointed to Donald Trump’s 13-member economic advisory team. Stephen Calk may have expected his foray into presidential politics to open new doors. Instead it backfired spectacularly.

The little-known banker became an important figure in the Russian election meddling saga, with prosecutors alleging that an executive who fits Calk’s description snagged a spot on the Trump advisory council in exchange for providing millions of dollars in loans to former Trump campaign chairman Paul Manafort.

Manafort, who is under scrutiny for his ties to Moscow, is scheduled to go on trial later this month on charges that include bank fraud. Calk, the CEO of the $265 million-asset Federal Savings Bank, could be a key witness at one of the most high-profile U.S. trials in recent memory.

Though Calk’s involvement in the Trump campaign did not go as planned, his own business history in Chicago may have given him reason to think that it would pay dividends.

Four years earlier, Calk struck an agreement with Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel that promised to bring up to 400 new employees to a gentrifying neighborhood west of downtown. The city agreed to pay the bank $10,000 per employee, in what was the largest-ever grant of its kind, to cover job training costs.

In the end, Calk and his brother John pulled off a neat trick: Their bank, among the most profitable in the country that year, collected $3.6 million in public subsidies in substantial part by rehiring employees who they had recently fired from a separate company that they also owned.

“It was blatantly obvious what they were doing, and how they got away with it is beyond me,” said a former Federal Savings Bank employee, who spoke on the condition of anonymity.

This article pieces together how it happened through publicly available court records and city of Chicago documents that were obtained under the Illinois Freedom of Information Act. The city and the bank said in written responses to questions that Federal Savings fulfilled all of its obligations, and that the funds were only paid after the job training was completed and verified.

Two companies, one address

Stephen and John Calk had long been the co-owners of a nonbank mortgage lender called Chicago Bancorp, which was headquartered in a six-story brick building in Chicago’s West Loop neighborhood.

In the spring of 2011, the Calks used a holding company they had recently formed to purchase a tiny bank in Overland Park, Kan. Generations Bank, which had just $44 million of assets, had not been profitable since 2007. Within a few months, the new owners changed its name to The Federal Savings Bank.

Stephen Calk later attributed his decision to get into the banking business to changes in the market and the regulatory environment for nonbank mortgage lenders. During a 2015 deposition, after being asked why purchasing the Kansas-based bank appealed to him, he lamented various costs associated with running Chicago Bancorp.

“The company had to be licensed in each individual state, which was very, very expensive and burdensome,” Calk said, “and then each one of the individual loan officers had to be individually licensed in each one of those individual states.”

“Furthermore, every loan officer had to have continuing education not only in what they did as their primary function, but they also had to take individual state licensing exams.”

Around the time of the bank acquisition, Stephen Calk told American Banker that the operations of the Kansas-based bank and the Illinois-based nonbank mortgage lender would be kept separate.

The Calk brothers also filed paperwork with the bank’s regulator, the Office of Thrift Supervision, stating that while they would serve on the boards of both their newly acquired bank and Chicago Bancorp, they did not anticipate any other relationships or transactions between the two companies.

“I planned to run a separate business,” Stephen Calk said in the 2015 deposition.

But court documents show that the Calk brothers quickly took steps to intermingle the two companies, both of which specialized in mortgage lending.

In the summer of 2011, Stephen Calk told the bank’s new regulator, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, that Federal Savings was planning to open a loan production office in the Chicago metropolitan area.

Also in 2011, key employees of Chicago Bancorp were assigned to generate mortgage revenue for the benefit of Federal Savings Bank, according to allegations laid out in a lawsuit that CitiMortgage later brought against the Calks and their companies.

The lawsuit charged that the president of Chicago Bancorp’s consumer direct mortgage division spent approximately half of his time running Federal Savings Bank’s consumer direct mortgage division during 2011 and early 2012.

By February 2012, Federal Savings had opened a Chicago office at 300 N. Elizabeth Street, in the same West Loop building where Chicago Bancorp had its headquarters, according to court documents. In fact, the two companies listed the same suite number — 3e — in their addresses.

Around the same time, Federal Savings reached out to the Mayor Emanuel’s office about the possibility of securing public funding to locate jobs in Chicago. Calk met Emanuel at the mayor’s office on Feb. 6, and a deal soon fell into place.

“It was blatantly obvious what they were doing,” said a former Federal Savings Bank employee.

Lots of money but little accountability

Emanuel, the former chief of staff to President Barack Obama, was first elected mayor of Chicago in 2011. He was keen on building a reputation as a job creator, and he quickly set out to eliminate a city tax that required businesses with more than 50 employees to pay $4 per employee each year.

“From now on, Chicago will no longer be a city that punishes job creation; we will promote it,” the mayor said in an October 2012 speech

Emanuel often ticked off the names of corporations that had moved their headquarters to the Windy City. Such relocations gave him an opportunity to tout the creation of new jobs and receive positive media coverage.

Some of the deals relied on tax increment financing, a mechanism that involves setting aside property tax revenue from a designated geographic area that can be used for economic development purposes.

In the nation’s third-largest city, the sums of money set aside are quite large. In 2016, Chicago reported $561.3 million in revenue from tax increment financing. Once collected, the money sits in a pot that can be used to subsidize private development.

Prior to Emanuel’s tenure, critics accused former Mayor Richard M. Daley of using TIF funds as a slush fund to reward his political allies.

After the City Council in 2010 approved a $15 million deal to pay for renovations at the Chicago Board of Trade, including refurbished restrooms, protesters gathered at City Hall to deliver a golden toilet. By the time of the protest, Emanuel had taken office, and the company that operates the Board of Trade soon said that it was not accepting the funds.

Emanuel promised greater transparency and oversight, and he did make some reforms, such as putting more information about TIFs online. But discontent over how the funds are distributed — the mayor and the local aldermen in particular TIF districts continue to exert strong control over the process — has persisted.

“It does open up a lot of potential and actual misuse of the funds,” said Amisha Patel, executive director of Grassroots Collaborative, a local nonprofit organization. “There is no accountability.”

Critics also argue that Chicago’s TIF program siphons away much-need money from local schools to finance development in gentrifying neighborhoods like the West Loop, where jobs would be created even without the help of taxpayer subsidies.

Eight tellers, training for 250 of them

On April 23, 2012, Stephen Calk said in an email to a city official that Federal Savings Bank’s board of directors had approved plans to establish a national home loan center in Chicago, subject to receiving a training allowance of $10,000 per employee.

“As discussed, we will endeavor to hire as many qualified Chicago residents as possible,” Calk wrote. “We are excited to be part of the Mayor’s plan to make Chicago an example for the rest of country.”

Under the deal, Chicago’s financial commitment was to come from a portion of the city’s TIF program that is dedicated to job training.

Between early 2012 and March 28, 2013, the city of Chicago awarded two TIFWorks contracts totaling $2.1 million to Federal Savings and its holding company, according to city records. The city awarded another $1.5 million to the holding company in October 2015, bringing the total to $3.6 million.

Federal Savings also had the opportunity to receive an income tax credit from the state of Illinois, potentially worth as much as $9.5 million, but that benefit never materialized. State officials determined that the bank fell well short of its goal of creating 300 jobs by the end of 2012.

Several weeks after Calk received the $10,000 per employee offer from the City of Chicago, Federal Savings filed a formal application that included details about how the bank planned to use the funds.

The bank’s application documents, posted on a city website, did not discuss hiring former Chicago Bancorp employees to work at Federal Savings.

However, a spokesman for the Chicago Department of Planning and Development told American Banker that the city was aware that the bank’s training would cover both incumbent and new employees. The program’s guidelines state that the funds can be used both to train new hires and to provide training that upgrades the skills of current employees.

Among the proposed expenditures in the bank’s May 2012 application was $1.07 million for regulatory compliance training.

That sum included the cost of enrolling 250 employees in a course called “Bank Secrecy Act for Tellers” — the intended audience was “bank employees who have cash handling responsibilities commonly associated with the teller position,” according to a course description. In the same application, the bank, which currently has two locations, only described plans to hire eight tellers.

A Federal Savings spokeswoman told American Banker that all employees of the bank are required to take the same Bank Secrecy Act training, regardless of job title.

The bank’s 2012 application separately proposed that taxpayer funds should be used to cover the cost of 250 employees enrolling in two additional courses on the Bank Secrecy Act, one of which was a general course and the other of which was intended for lenders.

Also included in the bank’s application was a proposal to spend approximately $487,000 on marketing and advertising as part of the hiring process.

Additionally, the proposed budget listed more than $160,000 for training in Microsoft Outlook, Excel and Word. And it included the unsupported assertion that email, spreadsheet and word processing training would result in such large efficiency improvements that the small bank would record more than $10 million in additional revenue each year.

“The expected effect of these courses is a 30% improvement in efficiency and communication,” the bank’s application stated.

‘Would they move to another desk?’

On the morning of June 28, 2012, Calk and Emanuel announced their agreement at a joint press conference.

Calk said that Federal Savings had decided to locate in Chicago after looking at sites across the country. He pointed his thumb at the mayor and said, “It’s probably no surprise to any of you here that this gentleman can be a very, very convincing guy."

When it was Emanuel’s turn to speak, he suggested that the city’s agreement with Federal Savings would expand Chicago’s workforce.

“It is banks, CEOs like Steve, who create jobs,” the mayor said. “It is our responsibility as a city and a state to be a partner by creating the atmosphere and the environment for companies to create jobs."

What went unmentioned during the press conference was that throughout 2012, Stephen and John Calk were taking steps to shut down their other mortgage lender.

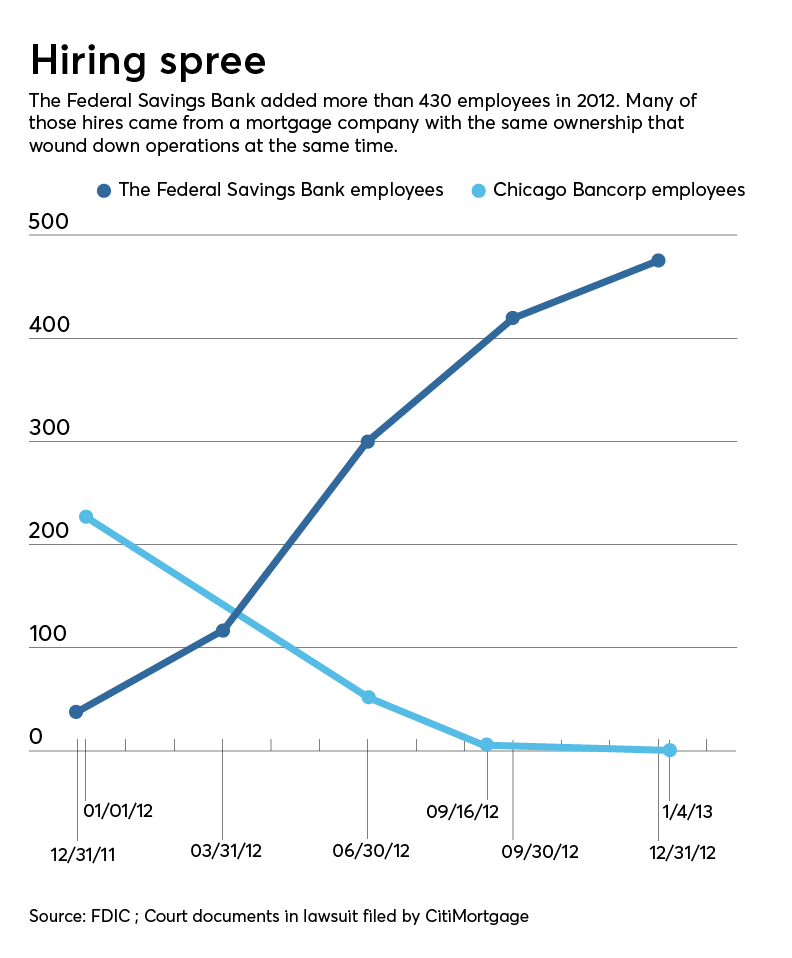

As of Jan. 1, 2012, Chicago Bancorp had 223 employees, according to court records. By June 30, the head count had fallen to 50. By Sept. 16, Stephen and John Calk were the only two employees remaining. On Jan. 4, 2013, the firm was formally dissolved.

An expert hired by CitiMortgage, which later sued the Calk brothers, calculated that 197 of Chicago Bancorp’s 223 employees at the start of 2012 were subsequently hired by The Federal Savings Bank.

According to data from Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., Federal Savings had just 38 employees on Dec. 31, 2011. Six months later, it had nearly 300, and by Sept. 30 it had close to 500.

“Are you aware that most of those Chicago Bancorp employees who left Chicago Bancorp ended up being employed by The Federal Savings Bank?” a lawyer asked Stephen Calk during a deposition.

“Yes,” Calk replied.

During the litigation, the Calk brothers said that they shut down Chicago Bancorp because tougher regulations were taking a financial toll on nonbank mortgage lenders. But CitiMortgage argued that the company had been profitable throughout the Great Recession, and that Stephen and John Calk received more than $10 million in distributions from Chicago Bancorp between 2007 and 2011.

In the lawsuit, CitiMortgage alleged that 11 loans it had purchased from Chicago Bancorp included misrepresentations of borrower income, inadequate documentation, or were faulty for other reasons. The case was eventually settled, and a confidentiality agreement has barred the parties from discussing it.

At one point during his deposition, Stephen Calk was asked a question that underscored the oddness of the Calk brothers rehiring employees who had recently been fired from one mortgage lender that they co-owned to work for another such company that was located in the office suite.

“Would they move to a different desk?” the plaintiff’s lawyer asked.

“I don’t know where that person would have been working,” Calk replied.

“Are you aware that most of those Chicago Bancorp employees who left Chicago Bancorp ended up being employed by The Federal Savings Bank?” a lawyer asked Stephen Calk during a deposition. “Yes,” Calk replied.

Two satisfied parties

Stephen Calk has been in the spotlight since early last year, when Federal Savings Bank mortgages to Manafort totaling $16 million were first uncovered. Earlier this year, prosecutors alleged that the longtime Republican operative lied on the loan applications, and that bank employees raised red flags, but an unnamed executive who is widely believed to be Calk overruled their objections.

Prosecutors have not accused Calk of any wrongdoing. But they did allege in a July 6 court filing that the bank executive sought a job in the Trump administration — Calk was reportedly angling to be named Army secretary but ultimately remained in the private sector — which factored into the decision to approve Manafort’s loan applications.

Federal Savings Bank has depicted itself as a victim of Manafort’s fraudulent conduct and said that it is cooperating with Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation.

When asked about the bank’s dealings with the city of Chicago, bank spokeswoman Kellie Kennedy said that Federal Savings hired 688 new employees in Illinois between 2012 and 2015.

Under the city’s job-training grants, applicants are encouraged to maximize the percentage of city of Chicago residents who receive training, and Kennedy said that 293 of the people the bank hired between 2012 and 2015 live in Chicago.

But when asked whether the city’s financial incentives were a factor in the decision to shut down Chicago Bancorp and rehire many of its former employees to work at Federal Savings, she declined to comment.

Kennedy did say that throughout the bank’s partnership with the city, The Federal Savings Bank met with city officials to discuss hiring and training and provided all necessary documentation to the city.

“The bank did not receive TIFWorks funding until documentation showed that employees were hired and trained,” she said in an email.

Mayor Emanuel’s office referred questions about its dealings with the bank to Peter Strazzabosco, a spokesman for the city’s department of planning and development.

Strazzabosco said in an email that the bank’s job training involved “250 new hires” and “157 existing workers.” The latter number is largely consistent with a 2014 email by a city official that said 160 people had been transitioned or transferred to Federal Savings from Chicago Bancorp.

But the June 2012 press release from Emanuel’s office that announced the deal made no mention of existing workers who would be transferred from Chicago Bancorp to Federal Savings Bank.

Strazzabosco said that no city funds were distributed to the bank until training was completed and verified. He declined last week to provide copies of that documentation, but said that it could be requested under the state’s Freedom of Information Act.

Late in 2012, Federal Savings reached out to city of Chicago officials to ask if some of the anticipated funds could be transferred by Dec. 31. “They need to get it by the end of the year — it affects their regulatory position,” Deputy Mayor Steven Koch wrote in an email to another city official.

“Against all odds, staff has gotten all the paperwork done,” came the reply a few days later. In the first of three payments from the city, Federal Savings received $1.33 million in late December 2012.

That same year, Federal Savings reported net income of $13.6 million. When the ABA Banking Journal published its list of the nation’s most profitable banks for 2012, Federal Savings finished first in its category.

The following June, Stephen Calk and Deputy Mayor Koch teamed up to write an op-ed piece for Crain’s Chicago Business, highlighting a recently released economic development study that cast Emanuel in a positive light.

“This is an important affirmation of where Chicago stands in the world economy and the efforts, led by Mayor Rahm Emanuel, to make Chicago into a more global city,” the two men wrote.

It was the least Calk could do.