High concentrations in commercial real estate could cause bankers to think long and hard about their next acquisition.

Consolidation has already been slow this year for reasons that include concerns over Bank Secrecy Act compliance, Community Reinvestment Act downgrades and potential sellers' hopes for rising interest rates. But warnings about heavy CRE concentrations may also play a role, industry observers said.

Regulators are paying close attention to institutions with CRE books that exceed 300% of total risk-adjusted capital. Given such scrutiny, banks that have already bulked up on commercial real estate loans may pause before buying another institution in a similar situation.

"Many banks have a high concentration of CRE and, from our view, some merger deals will be curtailed," said Vincent Hui, senior director at Cornerstone Advisors. "It will prevent CRE-heavy companies from acquiring other banks with a similar business model."

Some banks have already acknowledged the CRE concentrations have factored into their merger negotiations. Suffolk Bancorp, a Melville, N.Y., company with a large CRE book, said in a regulatory filing this summer that it rejected several potential deals because of concerns about the suitors' CRE concentrations. The $2.2 billion-asset company eventually agreed to sell itself to the $39 billion-asset People's United Financial in Bridgeport, Conn.

Management of Zions Bancorp. in Salt Lake City told analysts during its 2015 annual meeting that it would likely abstain from bank acquisitions due, in part, to the fact that many potential targets were too heavily concentrated in CRE.

Bigger banks with a "fair amount of real estate" may have to think more about buying smaller banks, which tend to be real estate heavy, said Brad Milsaps, an analyst at Sandler O'Neill. At the same time, a deal might not make sense if a potential buyer has to raise capital to offset an increase in the CRE-related ratio being watched by regulators.

While CRE could stymie some deals, it could also pave the way for others.

A CRE-heavy bank could use a deal to diversify their loan portfolio or to bring in more fee income, said Curtis Carpenter, a managing director at Sheshunoff & Co. Investment Banking.

"Banks that are heavily concentrated in CRE lending prefer targets that help out with that loan mix," Carpenter said. Buying a bank "with some agricultural lending or commercial-and-industrial lending…dilutes that ratio for them. That's the kind of target they want to find."

Hui agreed that some potential deals could actually "be accelerated" as regulatory scrutiny spurs some highly concentrated CRE banks to pursue deals that to diversity their loan mix.

While regulators would likely prefer to see a heavy CRE lender shrink the size of that loan book, they might also be willing approve a merger that derisks that institution's balance sheet, said Dallas Salazar, CEO of Atlas Consulting.

"Regulators could be more accommodating for M&A that constrains your capital but increases your reach," Salazar said. "Imagine an oil-and-gas or CRE lender buying a mortgage origination business. They can do that wherever in this country, so it's like buying diversity for their balance sheet."

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. declined to comment, though its policy statement on mergers notes that it will not approve mergers where a surviving bank "would fail to meet existing capital standards, continue with weak or unsatisfactory management, or whose earnings prospects, both in terms of quantity and quality, are weak, suspect, or doubtful."

The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency and the Federal Reserve did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

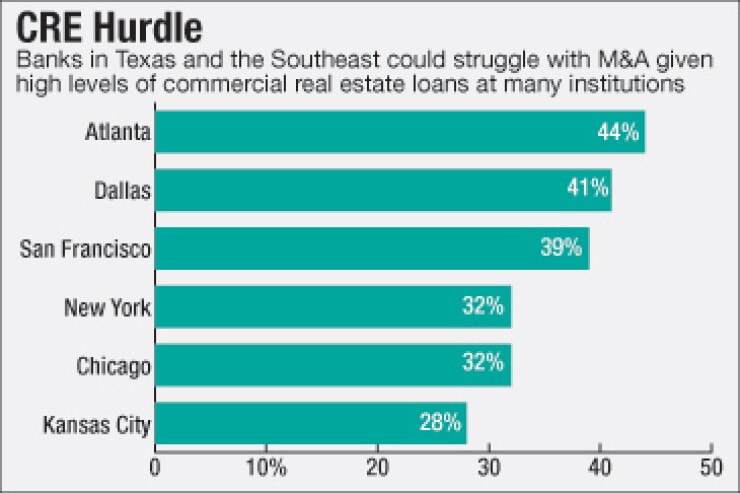

Several states could face bigger M&A hurdles given the high level of CRE on their banks' books.

Texas, which has already been hamstrung by concerns in the energy sector, could be particularly challenged, some industry observers said.

Many banks in the Lone Star State are "loaded up on commercial real estate," and buying an institution with a similar balance sheet could "exacerbate" that issue, said C. K. Lee, managing director at Commerce Street Capital in Dallas. "Until those questions are answered, we won't return to M&A."

Texas's population boom is responsible for banks loading up on CRE, Lee said. The state was home to five of the 11 fastest-growing cities and five of the eight markets that added the most people from July 2014 to July 2015, according Census Bureau data. That growth created a need for infrastructure such as shopping centers, office buildings and warehouses, which in turn led to more CRE opportunities.

Still, there are some deals that can still be done.

George Lea and Michael Thomas Jr. reviewed current regulatory concerns and guidelines before deciding to buy Trenton Bankshares in Texas. Most of Trenton's $97 million loan book consists of mortgages, according to FDIC data. The veteran bankers, who have raised enough money to buy the $165 million-asset bank, are planning to expand its reach by opening a new branch in Fort Worth.

"The regulatory guidelines are always on your radar," said Lea, who will serve as chairman and CEO of Trenton Bank once the deal closes. "CRE concentrations are something that we looked at…[as] we looked for the proper diversification of our loan portfolio."