Their entry

"Lots of power there, lots of intellect, and these companies understand digital," Hsieh said. "There's no doubt they're going to widen their products and services. You have big brands making bets to add products and services. You have real estate service and lending companies looking at each other: we're friends. Or will that turn into foe?"

It's understandable for lenders to be concerned. But if this incursion is so certain, why hasn't it happened yet?

Barriers prevent an easy entry to the business

Besides licensing, there are various forms of net worth requirements to be a mortgage banker, including state regulations, warehouse lenders and secondary market partners. Audited financials are usually required to show that lenders meet those requirements. While the costs may not be a burden for Amazon, going through the process is not a simple task.

On the compliance side, mortgage originators are subject to examinations by state regulators. There are also rules addressing quality control, appraisals, loan officer compensation and other forms of expenses that cut the net income from originating a loan.

Or it may just be that Amazon has simply been too busy to consider mortgages in between acquisitions like Whole Foods, its increasingly contentious development of a second headquarters on the East Coast and other ongoing efforts to branch out beyond online retail into entertainment, cloud computing, mobile technology and other categories.

But make no mistake, any industry where data and automation hold a unique advantage presents an attractive opportunity for large technology developers. And given Amazon's uncanny ability to understand consumers and deliver an exceptional digital experience, it may be able to succeed where so many others have tried and failed.

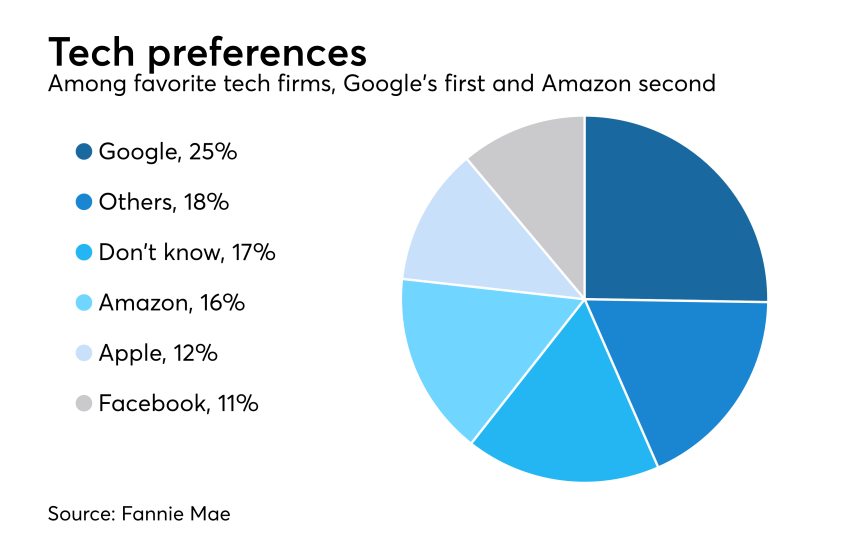

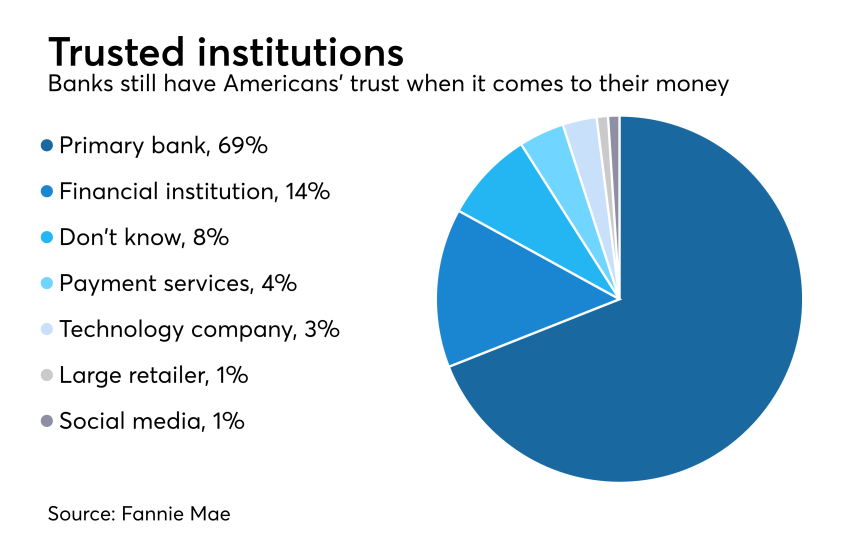

There is a willing audience that would turn to Amazon and Google for a financial product instead of a traditional provider, according to a recent Fannie Mae study.

Approximately 16% of all respondents, including 20% of those aged between 18 and 34, trust their favorite financial technology company to handle their mortgage, according to Fannie's third-quarter 2018 National Housing Survey. However, nearly two-thirds said they do not trust any of the big technology firms — Google, Amazon, Apple and Facebook — to provide any financial product out of concerns over data breaches and privacy.

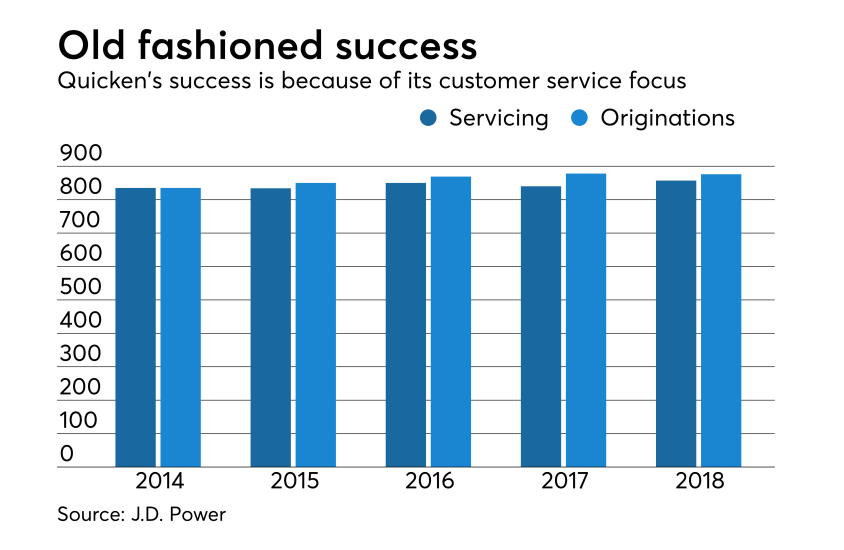

Other surveys indicated similar interest by consumers in using nontraditional providers for a financial product. Nearly 20% of consumers would use Amazon or Google for their home insurance, according to a J.D. Power survey released in August 2018. For millennials, that increased to 33% willing to use Amazon to obtain a property/casualty policy and 23% for Google.

Meanwhile, a 2012 study from Carlisle & Gallagher found one in three consumers said they would consider

"Amazon is a good example of a tech firm that has the ability to scale its platform across industries, and the mortgage industry is mired in legacy platforms," said John Cabell, director, financial services customer satisfaction at J.D. Power. "This combination makes it attractive for slick newcomers like Amazon and others."

Amazon declined to comment for this story. Still, plenty of big names — technology firms, traditional retailers and providers of other financial services — have tried and failed to bring mortgage under the corporate umbrella.

In most cases, their demise was related to housing market cyclicality, especially during the Great Recession. But now, what might be keeping tech firms out are the regulatory and compliance burdens of the business.

"These structures are daunting for newcomers. More than half of the mortgage origination customer experience is influenced by regulations, so lenders have to start with that template when creating a customer journey," Cabell said.

But some of that regulatory burden could shift because of the new

Employees of chartered fintechs that originate mortgages would be included under the SAFE Act, which exempts mortgage loan officers who work at covered financial institutions such as OCC-regulated banks from state licensing requirements — but they would still have to be registered with the Nationwide Multistate Licensing System.

Should tech firms make a play in mortgage, they would likely seek to differentiate themselves by creating a user experience that meets the desires of the millennial generation, the largest

"As we know, over the long term, distinctive value and customer experience are critical to success in any market," Cabell said. "The mortgage industry, lagging in customer adoption of digital usage by comparison with other financial services products, is no exception. Continuous improvement and adaptation now in this area are clear priorities for lenders as they plan for their future competition. Whoever that might be."

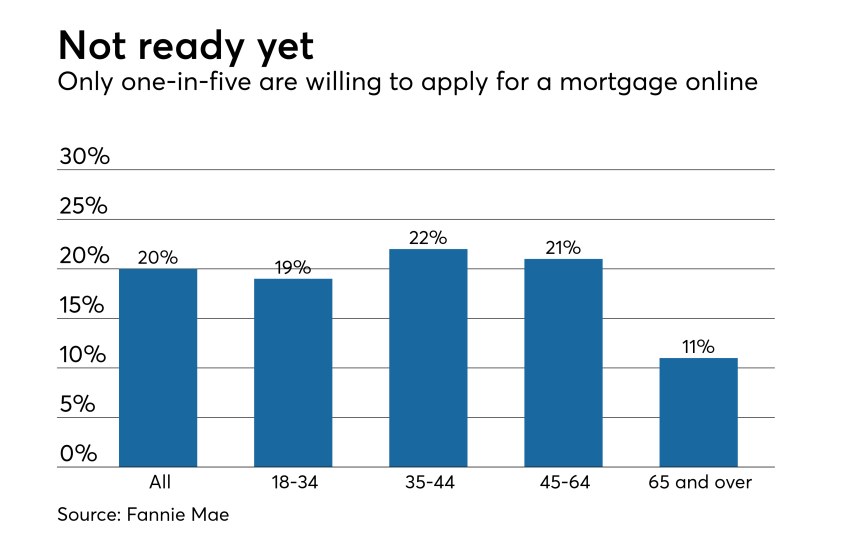

Consumers are looking for a digital experience

However, "lenders may be making big assumptions about what consumers expect or know about a digital mortgage experience," Cabell said about the results from a separate J.D. Power consumer survey conducted in late 2018 about digital mortgages.

"This industry uncertainty and the portability of technology expectations by consumers from retailers like Amazon may provide fertile ground for disruption," he added. "If traditional lenders are unable to crack the code on creating seamless mortgage customer experience that balances the best of human and digital interaction, then perhaps new entrants will do so first."

If Amazon does indeed enter the mortgage business, it won't be the first time it's gotten involved in a highly regulated, complex and expensive industry. It made a significant push into the public policy debate involving health care. During 2018, the company entered into

The joint venture "we hope will help improve the satisfaction of our health care services for our employees (that could be in terms of costs and outcomes) and possibly help inform public policy for the country. The effort will start very small, but there is much to do, and we are optimistic," Chase Chairman and CEO Jamie Dimon said in his annual letter to stockholders last April.

That announcement was followed by reports Amazon put out a

Amazon, so far, has partnered with existing companies for its financial offerings. That makes it a question on whether it would become a direct lender, like Zillow through its

The M&A route does have its own issues. "Skeptics have warned that Zillow will face an uphill battle," Cabell said. "Unlike Amazon, which has been on an equally ambitious journey to reinvent retail, Zillow is operating in the notoriously cloistered world of residential real estate, where many — even Google — have tried and failed to disrupt the status quo.

"It's not an easy business, and incumbents still have an edge when it comes to navigating the labyrinth of local contacts, entrenched relationships, and proven business models. But, the world and customer expectations are changing."

Google made a pair of attempts to enter the mortgage lead generation business. Not the financial success the company hoped for, it shut

The second try, done as part of the Google Compare product suite, was in conjunction with Zillow and LendingTree but it was short-lived —

Amazon's own reputation is at stake no matter which structure it chooses as its method of participating in the mortgage industry. Even before the social media era, a poor customer experience led to plenty of negative word of mouth campaigns.

Lenders are only as good as their last origination

Costco has an exclusive marketing relationship for its members to get access to mortgage loans with First Choice Loan Services. The parties work in conjunction with Affinity Partnerships, which monitors the participating lenders in the program.

"There is an old loan originator adage which goes something like this: In every loan application a major issue or a bomb is waiting to go off, and it is the responsibility of the loan officer to defuse it before it does," said Affinity Partnerships president and CEO John Alexander. "Our mission is to ensure Costco members have lenders who they can trust and are looking out for their best interests. When we do that, everyone wins."

Costco is not affiliated with either First Choice or Affinity Partnerships, nor is it responsible for any of the activities of the participating lenders. Alexander is also a director of First Choice.

Costco members access the program through a website. It has been in existence for 10 years, and it was recently renewed with a multiyear agreement.

There is an oversight provider to ensure participating lenders are focused on the needs of Costco members and that they are "being treated in the Costco way," Alexander said.

"To us it means each lender and their team must focus on doing what is right for the member first and foremost. In many cases, this impacts lender profitability. This is clearly not the most profitable for lenders and the demands for service are extremely high."

Costco "has a heightened standard of customer service and value. Aggregated information is shared with them to assure them their members are happy and they're getting the value and the service they expect when they walk into a Costco warehouse," Alexander said.

Besides First Choice and its parent Berkshire Bank, other lenders participating are J.G. Wentworth Home Lending, Lending.com, Strong Home Loan and NBKC Bank.

Affinity Partnerships monitors and shares metrics about customer service with the participating lenders on a weekly basis. Companies that fail to meet those metrics have been removed from the Costco partnership.

Many models to choose from

Another option is to create a mortgage brokerage franchise business along the lines of Remax Holdings' Motto Mortgage.

In less than two years, Motto has

Motto is not licensed as a mortgage company. Each individual franchisee is responsible for compliance and licensing. Even though the legal risk is mitigated, the reputational risk remains.

Zillow's acquisition of MLOA was motivated by a desire to offer mortgages in its home flipping business, rather than the broader consumer market, the company said. Still, the National Association of Federally-Insured Credit Unions used the Zillow deal as the reason in a letter to the House Financial Services Committee why fintech companies

Zillow was looking for institutional knowledge and experience when it decided to get into mortgage lending. "We certainly realize our strength today is in technology," said Erin Lantz, vice president of mortgage at Zillow. "That's why we wanted to acquire a company with a seasoned team and a long history of successful purchase originations throughout business cycles."

As a mortgage lead generator, Zillow was already licensed as a mortgage broker in 40 states and the District of Columbia. But it didn't originate loans using those licenses.

"The most comparable type of company for what we're doing with Zillow Offers and mortgages are homebuilders, which have a long and rather successful history building and then selling homes and then also providing mortgage to the buyers of those homes through

Zillow's name attracts consumers like a "bug zapper" to search for properties said John Campbell, managing director at Stephens. "Zillow's approach over the last two years is aggressively moving down the funnel" into other portions of the real estate transaction and this deal fits that mold, he said.

MLOA "makes that bug zapper tool much better for the sell side" of the real estate transaction, Campbell said.

Even for digital-forward lenders, service drives reputation

After the acquisition, those businesses were combined and Rock Financial was renamed Quicken Loans. However, in June 2002, Intuit, because it changed its marketing focus to small businesses from consumers, sold the mortgage lender back to a

While Quicken Loans has been in the forefront of the

Others left the mortgage industry as part of a refocusing back to their core business during a down cycle.

Online mortgage marketplace LendingTree got into the business through the

But in 2011, in the midst of the down real estate cycle and deciding to get back to its roots in the lead generation business,

It took Discover only three years to realize the mortgage business

And for the record, Discover's former corporate parent, Sears, bailed on the mortgage business in 1993, as part of a broader divestiture of all its financial business as the retailer, troubled even back then, looked to refocus and save money. Sears, already the parent of Allstate, decided in the mid-1970s to expand its financial services footprint (including owning a real estate company) as an extension of its retail business.

Some other big names that pulled out of mortgages: General Electric, GM, Prudential, Ford and H&R Block.

GE, which left the prime mortgage business around 2000, purchased

GE

GE also owned a mortgage insurer, which it — along with its life insurance business — spun off into Genworth Financial in 2004 to focus on higher growth businesses.

General Motors was hit hard by the recession and the automaker was forced to file for bankruptcy in 2009. Its mortgage businesses were heavily weighted toward originating and servicing

Before the mortgage crisis, Option One Mortgage was

In 2001,

Even travel website Priceline entered the mortgage business, holding

Another option for a nonfinancial company like Amazon getting into mortgages is to go the private-label route, and hire an outsourcer to do the work in its name. But the reputational and regulatory risk remain.

"There are multiple ways for big tech firms to compete with traditional banks in consumer finance, including using their digital prowess to move online more of the complex and costly experiences that consumers today prefer to do via personal interaction, and in ways that offer a better overall experience," Fannie Mae's director of market insights research, Steve Deggendorf, said in a blog post. "Now is the time for banks to step up their digital game and, more specifically, to consider how to best digitize more complex financial tasks before big tech does."