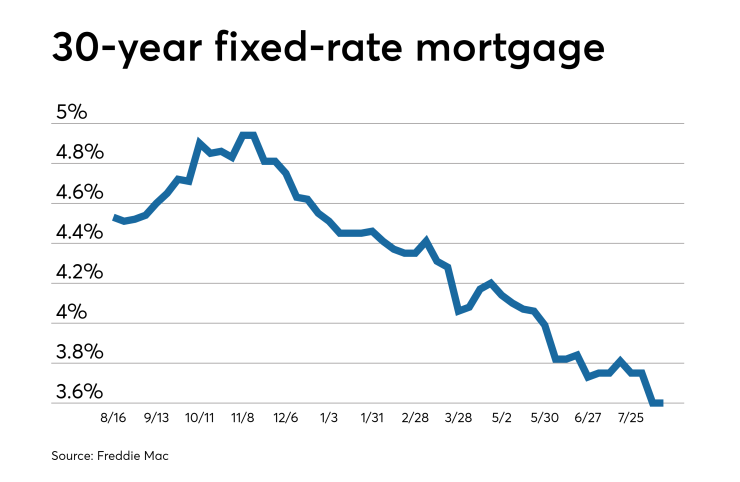

Since 2008, the U.S. mortgage industry has been buffeted by a great many changes and a lot of volatility and risk in the financial markets. The chief source of risk to the world of mortgage finance, for example, now comes from monetary policy and the Federal Open Market Committee. Witness the precipitous drop in yields on the 10-year Treasury note and with it 30-year mortgage rates.

At the start of 2018, mortgage refinance transactions were about 10% of total volumes. Just eight months later,

There is not much visibility on mortgage volumes or prepayment rates much beyond Halloween. Suffice to say that the industry does not need more uncertainty. Wide short-term swings in interest rates — and loan prepayments — that we've all witnessed have serious secondary effects on consumers, lenders, investors and also policymakers.

Last year,

"It makes no economic sense," he fretted to NMN. "There are some anomalous characteristics here, one of which being this spike in refinance activity is happening right at month seven." At the time, VA loans could only be refinanced after being seasoned for six months, thus prepayments tended to rise sharply in “month seven” with a focus on cash-out refinancing.

Ginnie Mae ultimately punished several large servicers for allegedly engaging in aggressive practices when it comes to refinancing VA loans, which caused prepayments on some GNMA securities to spike. These issuers were not able to sell VA loans into multi-issuer RMBS for a period time. Those sanctioned were chosen based upon a statistical formula that compares an issuer's prepayment rates with its cohort sorted by the loan coupon. The nonbank issuers were apparently given ample warning of GNMA's actions, but complained none the less. They argued many VA loans were already "in the money" for a rapid refinance long before interest rates fell.

Clearly Bright came under political pressure on Capitol Hill during his July 2018 confirmation hearings. Some in the mortgage industry thought that Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., who just happens to be seeking the White House in 2020, bullied Bright and Ginnie Mae into penalizing a number of lenders for alleged "churning" VA loans. But in fact, due to pressure from investors and the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association, the agency was already moving to impose penalties long before Warren began to yowl about "churning."

Though GNMA has a statutory responsibility to facilitate mortgage finance and protect the taxpayer from loss, it also worries a lot about how investors view the agency's mortgage securities. As one industry veteran told NMN: "This prepayments issue is all about TBA eligibility and investor interests."

The question of loans being eligible for delivery in the "to-be-announced" market for future GNMA securities is important. Investors in GNMA securities like the Bank of Japan don't know the exact makeup of the loan pools in a given security. When prepayments on the securities are three, four or five times the expected rate, though, big investors lose money and the phone starts to ring at GNMA. This problem is so serious for some investors that SIFMA considered making multi-issuer GNMA pools ineligible for TBA altogether.

According to a report by Laurie Goodman at the Urban Institute, faster prepayment speeds caused by the alleged churning, if passed on to all borrowers, would require all Ginnie Mae borrowers to pay an additional seven basis points per year in interest rates. Goodman also noted "Ginnie Mae should take further action to reduce this churning but must also ensure that its solutions [do] not impose significant costs on the mortgage system or pick winners and losers."

The good news is that HUD has apparently taken the advice of Goodman and others about no longer picking "winners and losers” and instead is focusing on adjusting the actual lending program. HUD recently took action "designed to reduce risk associated with cash-out refinance lending" and any concerns about prepayment rates from investors. Specifically, the FHA will

Ginnie Mae's focus of programmatic adjustments is a welcome change. Blaming individual mortgage servicers for high prepayment rates is neither fair nor an effective way to manage this issue — especially when Ginnie Mae lacks all the data on loan recapture to actually understand who is making the new loans that cause the prepayments.

Large mortgage lenders actually buy much of their production from other lenders, third-party originations or "TPO" in industry parlance. These large issuers then sell their loan pools into securities with other issuers. Ginnie Mae tracks prepayments by issuer. Whether or not a Ginnie Mae issuer services a mortgage, however, does not necessarily mean that servicer has the inside track to refinance that particular loan. GNMA requires large aggregators to discipline or even terminate TPO lenders who have high prepayment or delinquency rates.

Historical "recapture" rates by servicers on government insured mortgages that prepay early are quite low. We're talking in the 20% range for the industry in terms of purchase loans, higher for mortgage refinancing depending on the type, issuer and geography. If a large servicer of VA loans even gets a chance to compete for one out of every two or three loans in the portfolio that refinance, that's a lot. And oftentimes a TPO partner is the culprit.

Policymakers concerned about improper loan refinance behavior need to appreciate that the largest servicers are also owners of tens of billions of dollars' worth of mortgage servicing assets — assets purchased from mostly from TPO channels. Indeed, mortgage servicing is the chief capital asset of nonbank mortgage firms. Servicers of GNMA securities are also investors.

When prepayments rise suddenly thanks to the action of the FOMC, owners of servicing assets are forced to scramble to make and/or acquire more loans to replace the runoff. As we noted in a

Rate volatility and prepayments have only intensified since last month. "MSRs are being capitalized at a 4x multiple but coupon swaps imply a 2x," notes industry veteran Alan Boyce, commenting on 2Q earnings. "So mortgage bankers are pooling with maximum excess servicing and selling into the lower coupon execution (4% loans going into FN 3s)."

Consider the irony: a large loan aggregator could see an in-the-money mortgage picked off by a smaller lender in a refinance transaction, then end up buying the new mortgage note and related servicing in the secondary market from that same TPO. Even if that loan has been in portfolio for a year or two, it is at best break even to the owner of the servicing. If there is truly a victim of loan churning, it is the equity investor of the largest residential loan servicers and REITs.

GNMA's approach to adjusting the criteria for mortgage refinance transactions is the right way to address the prepayment issue with VA loans. In the longer term, however, it may be a good idea for the mortgage industry to move away from multi-issuer pools and again have large aggregators do most of their production via "custom" or single issuer pools.

Not so many years ago, most GNMA issuers sold their own securities directly to investors. Today the political sensitivity of the prepayment issue and the potential damage that can be done to issuers that are sanctioned by GNMA for "churning" are seemingly two very good reasons for issuers to move away from the multi-issuer program as quickly as possible.