It is a bold claim: Banks could potentially originate 300,000 more home loans per quarter without taking on too much more risk.

That is the latest prediction from Laurie Goodman, the director of the Urban Institute's Housing Policy Finance Center. Goodman, a former Wall Street analyst, has been on a mission to prod banks to make more loans to borrowers with low credit scores.

Credit is so tight now, Goodman argues, that banks and mortgage lenders would need to increase lending by 50%, or to get back to normal, pre-bubble levels. Though lending to borrowers with credit scores below 660 would raise the risk of defaults, it would still be within "tolerable limits," Goodman said.

Many borrowers with lower credit scores fall within the guidelines set by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and the Federal Housing Administration, she said. Lenders are often unwilling to make such loans out of fear they will have to buy them back it the borrower does default.

"Banks are lending more narrowly than they have ever done before," said Goodman, a former managing director at Amherst Securities. "We would generate a lot of additional lending if lenders lent to the full extent of the Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Federal Housing Administration credit boxes — something that they aren't willing to do."

Other analysts agree that credit is tight, but they don't expect banks to relax credit standards any time soon.The Federal Housing Finance Agency, which oversees Fannie and Freddie, revised guidelines to give lenders more clarity on mortgage buybacks. The changes, which were lobbied for heavily by banks, are expected to prompt lenders to loosen credit standards but could take some time to implement.

"Is credit too tight? Probably," said Chris Flanagan, head of U.S. mortgages and structured finance research at Bank of America Merrill Lynch. "Is it going to change? Probably not. It's going to change very slowly."

Lenders have been forced to buy back billions of dollars in loans from Fannie and Freddie, and to indemnify the FHA, for loans that do not meet the agencies' underwriting standards.

"Right now the credit box is far more restrictive than anything we had in the early 2000s," Goodman said. "It's a jillion little things... and one by one [regulators] are solving [the problems], but it takes time."

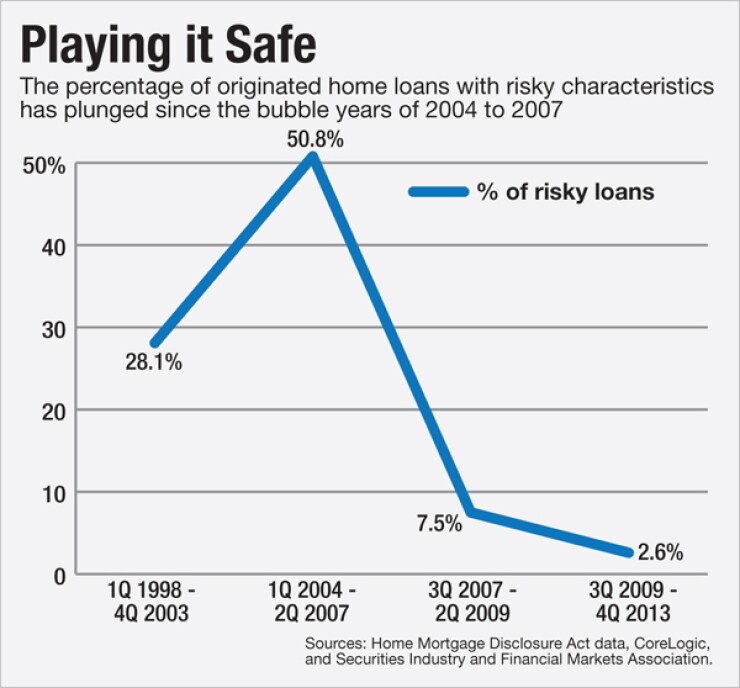

One of Goodman's core arguments is that credit remains tight even though risky loans with unsustainable terms were eliminated by the Dodd-Frank Act. Risky features such as interest-only loans and adjustable-rate mortgages with balloon terms, negative amortization and prepayment penalties were all wiped out by that 2010 law.

Loans with risky features accounted for 50% of all mortgage volume during the bubble years. But post-crisis, risky loans now make up just 2.6% of all single-family home loans, according to a report Goodman released last week.

With risky loans gone from the market, lenders should have far less risk and could make more loans to borrowers with lower credit scores, Goodman argues.

"You don't have the risky characteristics and yet the credit box is much more limited, which suggests there is room for lenders to eliminate credit overlays and still have risk at an acceptable level," Goodman said.

Lenders have set their own internal "credit overlays," which are minimum credit scores above what is allowed by Fannie, Freddie and the FHA. These credit overlays, typically a FICO score of 660 or 640, have locked many potential homebuyers out of the market.

Recently Goodman and Wei Li, a senior research associate at the housing center, created a way to measure how much banks are willing to extend credit at any given point in time. Tracking the risk of default over four periods — pre-bubble, bubble, crisis and post-crisis — they found the current default risk on all loans is 6.7%, down from 16.6% at the height of the crisis in 2007 to 2009.

Crunching the numbers to define the risks in the market may not matter much. Some analysts see a larger paradigm shift at work.

"There's a supply side and a demand side to mortgage credit," said Flanagan. "Everybody is focused on the supply side, the bank side, but there is a whole generation of people on the demand side that are not that interested in getting a mortgage anyway. They don't have the income and savings to get a mortgage."