Efforts to revive the private secondary market for home loans could stall this year as

More than half of all home loans originated today have minor errors that are not compliant with the "Know Before You Owe" consumer disclosure rule that went into effect Oct. 3, according to Fitch Ratings. Roughly 5% to 10% have major compliance problems, while just 25% to 30% are fully compliant, Fitch said.

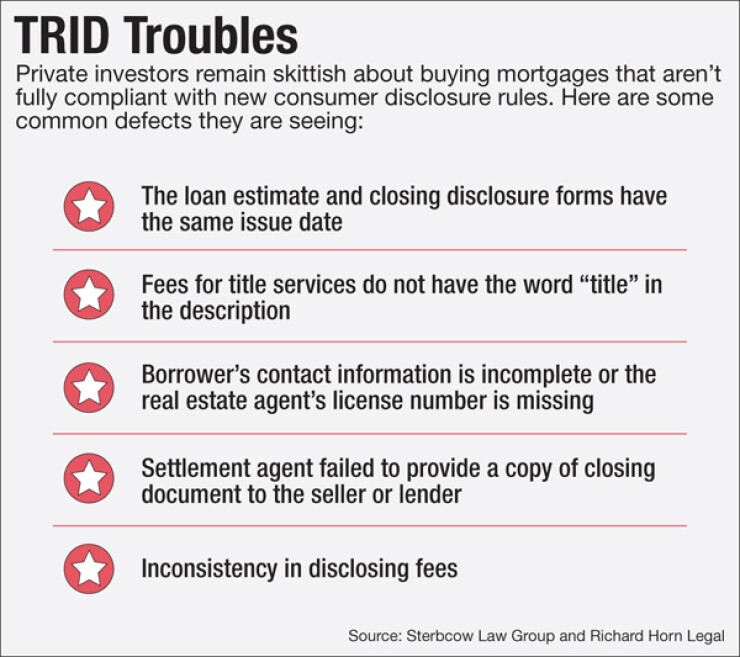

The rule — a combination of the former Truth-in-Lending and the Real Estate Settlement Procedures acts commonly known as TRID — was meant to help consumers understand the total costs of a home loan. Because there are hundreds of variables to account for on the forms, compliance has become a near-impossible task. As a result, many investors are refusing to purchase loans without further guidance from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

"What's at stake here is that we just went through a financial crisis in the mortgage markets, where secondary market participants, investors and the government would frequently require that loans be repurchased or indemnified for losses based on noncompliance with highly technical regulations or requirements that may have had nothing to do with the default of the loan," said Benjamin K. Olson, a partner at the Washington law firm BuckleySandler and a former deputy assistant director in the CFPB's office of regulations. "Given that history, the current reluctance to accept even the most technical TRID violations is entirely rational."

The pullback by investors could further the slow the issuance of private-label mortgage bonds this year, a huge concern at a time when the vast majority of home loans today are insured by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac or the Federal Housing Administration, experts say. Just $547.2 billion in private mortgage bonds were issued in 2015 for jumbo, Alt-A and re-securitized home loans, compared with $1.7 trillion in 2007, according to the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association.

There is already some fallout. Last month, Redwood Trust, a Mill Valley, Calif., real estate investment trust that purchases loans for securitization

"Whether we can get a more robust private secondary market in mortgages will depend a lot on whether the industry can get to a place where it's comfortable with the risk associated with TRID violations," said Olson. "Secondary market participants and their diligence vendors are trying to work through how to deal with the fact that if you are not buying loans with TRID violations, you're not buying many, if any."

The refusal by some investors to purchase loans also is hitting nonbank lenders that sell to secondary market investors as loans get stuck on their warehouse lines or get sold at a discount, cutting into profits. Experts also are warning that banks could be affected. There is concern that large banks that originate and hold jumbo loans on their balance sheets could have problems if they try to securitized loans down the road that don't meet TRID requirements.

"This is an issue for the entire market," said Richard Horn, a former senior counsel and special advisor at the CFPB who runs his own law firm. "Investors are extremely conservative with the types of loans that they'll accept and this applies to agency loans [backed by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac] as well as jumbo. It's definitely an issue for jumbos, and that's being felt by a number of lenders."

The risk of having to repurchase a loan that does not meet guidelines also is reemerging as a concern among large bank aggregators like JPMorgan Chase and Wells Fargo. Though Fannie, Freddie and the FHA

Stephen Ornstein, a partner at the law firm Alston & Bird, said that while Fannie, Freddie and FHA have given the industry some leeway, there is still a requirement to comply with the law.

"I wouldn't take it for granted that there's going to be leniency forever when you're selling loans to Fannie and Freddie," Ornstein said. "If you are selling a loan and it's not compliant you are going to face a putback."

To be sure, lenders are moving quickly to resolve errors; just two months ago, Moody's Investors Service reported that roughly 90% of loans had compliance problems. Both Olson and Horn also expect the CFPB to issue additional guidance on TRID.

Until that happens, though, investors are relying heavily on their lawyers to help them make tough decisions about whether to purchase loans with TRID violations.

Olson wrote

"I don't believe TRID compliance will ever become perfect," Olson said in an interview. "There are too many moving pieces and it reflects a transaction that is incredibly complex and idiosyncratic at the loan level."

The costs for violators are steep, which is one reason investors may be rejecting so many loans.

For lenders, the CFPB can impose civil money penalties of $5,000 per day per violation for noncompliance, $25,000 per day for reckless violations and $1 million per day for knowing violations. Such fines do not apply to trusts, but they fear being sued by their investors in the event of loan losses.

TRID does expand the amount of potentially erroneous information that a residential mortgage-backed securitized trust could be liable for.

Though a borrower who goes into foreclosure could eventually sue a lender for a TRID violation, not all violations are subject to statutory damages for individual claims of up to $4,000. It would be hard for borrowers to recover actual damages for many minor violations, lawyers say. Class action damages of up to $1 million are possible, though it would be difficult to establish commonality among a class of borrowers given the wide range of TRID violations.

Still, one of the reasons most investors have zero tolerance for violations is that most agreements for the sale or securitization of loans have "reps and warranties" that say the loans comply with all applicable laws and regulations, Horn said.

"If there is any violation, no matter how minor, it results in damages under the agreement, including repurchase or buyback risk for the originator, middleman down the line," Horn said.

John Levonick, the chief compliance officer at Clayton Holdings, a Shelton, Conn., due diligence and consulting firm that is a unit of mortgage insurer Radian Group, said there are no definitions for non-numerical clerical errors and whether they can be cured. Due diligence firms are hired by investors to help identify errors.

"At the end of the day, it's the investor or whoever is acquiring the loan that determines whether to accept or reject the loan," Levonick said. "But it really depends on the risk tolerance of the investor. Some only want pristine loans and some have a higher risk tolerance and will accept loans that have deviations where their exposure could be mitigated or they've priced in the risk."