If examiners were to raise a stink about his commercial real estate loan concentrations, Bob Mahoney at Belmont Savings Bank in Massachusetts is ready to get down and dirty.

Using big data, the head of the $2 billion-asset bank is trying to keep tabs on all 380 tenants in properties where it is the commercial mortgage lender. If an accounting firm in an office building is named in a lawsuit, Mahoney is alerted. If a dental practice has its credit score downgraded, he knows about it.

"This lets us create a list of tenants — here are the high risks and here are the low risks," said Mahoney, who is using software from Dun & Bradstreet to flag risks early.

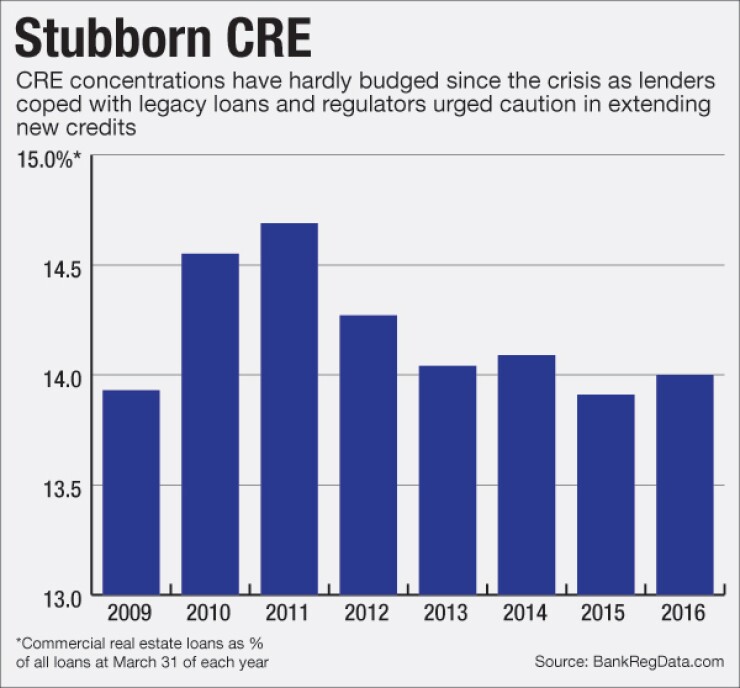

Many banks are girding themselves for probing questions about CRE-related risk management. Commercial real estate, as a percentage of the industry's total loans, remains stubbornly high, and examiners are said to be peppering bankers with questions about how they plan to avoid the kind of meltdown that took place in such portfolios nearly a decade ago.

Regulators want banks "to have both a high-level view and a detailed view of the risks and potential losses" associated with CRE lending, said Matthew Anderson, a managing director at Trepp, a D&B rival that sells software to banks for monitoring and stress-testing CRE loans.

"The approaches [lenders] had been taking are now deemed as not sufficient," Anderson said. Regulators "want more analytical rigor."

Red Flags from Regulators

Regulators have made their concerns no secret.

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. warned bankers in July about the rapid expansion of multifamily lending; regulators classify multifamily loans as a subset of CRE.

The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency's spring 2016

Representatives of the FDIC and OCC declined to offer additional comment.

Even more wide-ranging was an

Growth Pressures

Yet bankers are not going to give up on commercial real estate. There is little room for growth in other lending areas, and CRE provides good returns.

"We view CRE as a core competency of our franchise and do not see this emphasis changing," David Black, chief credit officer at the $3.6 billion-asset State Bank Financial in Atlanta, said in a July 28 conference call.

While banks can book big profits by rapidly building up CRE portfolios, it is a risky proposition, Dennis Hudson, chairman and chief executive at the $4.4 billion-asset Seacoast National Bank in Stuart, Fla., said during a July 28 conference call.

"We have put into place, and are following mechanisms and policies, and ensure this will not happen at Seacoast," Hudson said.

Role of Data

This is where big data can come into play. Numerous companies provide software to banks that let them analyze commercial mortgages in exhaustive detail, including Altus Group in Toronto, and Hightower and REIS, both in New York. Altus, Hightower and REIS did not return calls seeking comment.

Dun & Bradstreet's commercial tenant credit monitoring product lets banks create credit-scoring models on tenants, based on criteria such as whether a tenant will pay its bills on time, said Joe Panunto, senior vice president of financial services. D&B gets the data from its own proprietary databases and from publicly available sources.

Belmont Savings has implemented the D&B scores as the fourth data point in its official underwriting policy for CRE lending, Mahoney said. The other data points are a tenant's cash flow, loan-to-value ratio and the quality of the landlord.

Mahoney declined to say how much the bank is paying Dun & Bradstreet for the software.

Time will tell how accurate such products prove to be.

It is a tall order for D&B to say that they will provide a banker with up-to-the-minute details on smaller tenants, said Suzanne Mulvee, research director at CoStar, another D&B competitor.

"I suspect their information gets a little stale," Mulvee said. "I think they would have to rely on lagging indicators instead of leading indicators."

CoStar's products, in contrast, help banks evaluate broader market trends, such as specific markets' occupancy levels, rent-pricing schedules and vacancy rates, Mulvee said.

Mahoney acknowledges that there are limits to the software he is using. But it provides a big assist when Belmont is in the decision-making process about issuing a new mortgage. Belmont Savings' credit committee earlier this month used the D&B reports to make decisions on three separate transactions.

"If something comes up as a red flag, I might require a bigger loan guarantee, or I might lower the loan-to-value ratio," Mahoney said. "Or you might shorten the loan to three years from five years."